"Never forget that under a totalitarian system cruelty and absurdity go hand in hand." Ai Weiwei. 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows (p. 137)

"In China, if you try to understand your country, it’s enough to put you on a collision course with the law." (p. 147)

"Young people in China today have no knowledge at all of the student protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, and if they knew they might not even care, for they learn submission before they have developed an ability to raise doubts and challenge assumptions." (p. 204)

"It’s a mistake to always take me seriously. (p. 217)

"In 1910, the year my father was born, my grandfather had just turned twenty-one. The Qing dynasty was nearing the end of its 266-year rule, while in Russia the fall of the czars and the advent of the Soviet regime were just seven years away. It was the year that Tolstoy and Mark Twain died, the year that Edison invented talkies in faraway New Jersey. In Xiangtan, in Hunan, seventeen-year-old Mao Zedong was still in school; his first wife, selected for him by his parents in an arranged marriage, died a month before my father was born. But Fantianjiang, like so many other Chinese villages, slumbered on, unremarkable and anonymous." (Ai Weiwei. 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, p. 17).

"In this era of dreary routine and material scarcity, the kitchen served as the focus of people’s imagination, even if little changed from one day to the next. Each morning the cook would mix cornmeal with warm water and place the dough into a meter-square cage drawer, then stack five such drawers inside an iron pot and steam them for thirty minutes. When the lid was lifted off, the whole kitchen would fill with steam, and the cook would carve up the corn bread vertically and horizontally, each square piece weighing two hundred grams. To show his impartiality, he would weigh the blocks publicly. This same corn bread would be served from the first day of the year to the last, except on May 1 (International Workers’ Day) and October 1 (National Day), when the corn bread would acquire a thin red layer, made up of sugar and possibly jujubes. If someone was lucky enough to find a jujube in their corn bread, this would always stir some excitement. The company had large expanses of cornfields, but we never once had fresh cornmeal to eat, only 'war-relief grain' that had been in storage for goodness knows how long: it scraped your throat roughly as you swallowed, and reeked of mold and gasoline." (p. 12).

Eventually, Mao had no more use for intellectuals: "the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957... marked the end of intellectuals as a force in society. From that time on, Chinese intellectuals were confined to a marginal position, and they have been there ever since." And it still burdens the freedom of thought of Ai Weiwei: "Ideological cleansing, I would note, exists not only under totalitarian regimes—it is present also, in a different form, in liberal Western democracies." (p. 83-84)

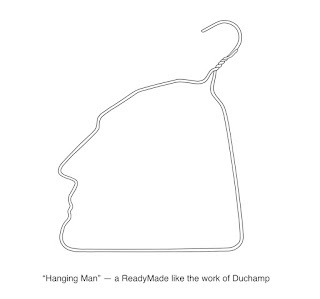

After describing the experiences of his father, Ai Weiwei continues with his own story. He was born in 1957, when his father was 47 years old, and he lived in exile with his father for a major part of his childhood and youth. Wanting a broader education the young Ai Weiwei managed to get to Philadelphia to go to college. Here, at the famous art museum, he encountered one of my favorite artists: Marcel Duchamp, who along with Andy Warhol became a critical influence on his development as a conceptual and otherwise off-beat artist -- for me one of the most fascinating aspects of the book.

"In one of the galleries, a bicycle wheel was mounted on a wooden stool; two large panels of glass, one above the other, each splintered and cracked, invited you to contemplate the relationship between the “Bride’s Domain” above and the “Bachelor Machine” below." (p. 168).

Ai Weiwei's description of his development as an artist and his view of art make up a major part of the rest of the book. He explains:

"Art had long been a consumption commodity, a decoration catering to the tastes of the rich, and under commercial pressures it was bound to degenerate. As artworks rise in monetary value, their spiritual dimension declines, and art is reduced to little more than an investment asset, a financial product." (p. 176).

Along with his self-invention as a political activist as well as being an artist, he used provocative actions (or "little acts of mischief") as a way of public expression, influenced by Warhol and others including Alan Ginsberg. Adapting to the modern age, Ai Weiwei became a blogger with a huge following; when the Chinese authorities shut down and destroyed his blog, he became a Twitter user, always advancing his views of art and political issues with bravery in the face of the repressive Chinese authorities.

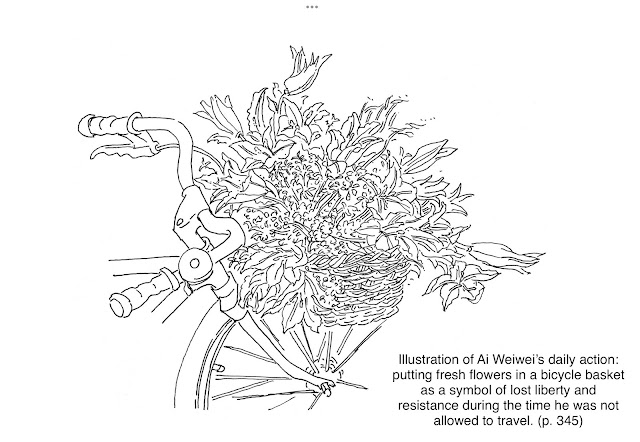

Finally, the government subjected Ai Weiwei to 80 days of imprisonment with brutal policemen constantly questioning and badgering him for 24 hours a day. After his release he was not allowed to leave the country for several years, and his artistic endeavors were disrupted. He cultivated attention to his mistreatment in a variety of ways, and was finally released. He has now moved to Europe, where he continues to be a productive artist.

|

| The memoir is illustrated with sketches by the author. The bicycle basket action was photographed every day, and posted on Instagram as a symbol of his lost freedom. |

An Exhibit of Ai Weiwei's Art

|

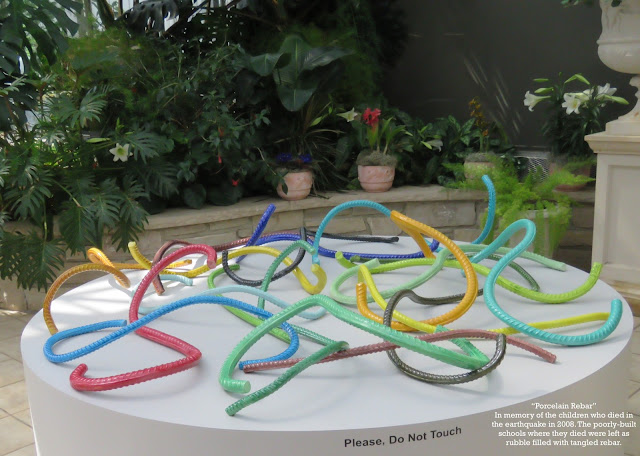

| In 1995, one of Ai Weiwei's public actions was to drop and shatter a Han-Dynasty urn. This was the subject of one room of the exhibit in Grand Rapids. |

4 comments:

This is fascinating, Mae. I know little of his past or of the Chinese communist government of that period and so it's really an eye opener -- and that's your review. What a remarkable lot of experiences in his life. His work is certainly remarkable. How lucky you were to see this exhibit.

SUCH an interesting post. You do live an interesting life.

BTW, just want to say we've just posted our last blog post. I've thoroughly enjoyed your blog, and I'll still be visiting. But we've got a lot of activities lined up that will be occupying my time, so my visits will be much more sporadic in the future. Best wishes to you.

I cannot imagine how much his father must have suffered even though I've read numerous books about the camps and their conditions.

Love this post. I was fortunate to see him and some of his art pieces and documentary film when they were featured here in San Francisco. Definitely one of the great artists of this time.

Post a Comment