Friday, November 09, 2012

Calder's Fork

In the Los Angeles Times Today: "Alexander Calder's fanciful kitchen utensils" -- he'd make them for his wife when she needed something. I'm a big fan of his fanciful wire and metal objects, such as portraits and his circus. I wonder if I can find the book, Calder at Home, that these images are from.

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

Franz Werfel: The Forty Days of Musa Dagh

“The most horrible thing that had been done was not that a whole people had been exterminated, but that a whole people, God’s children, had been dehumanized.” – The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, 2012 edition, p. 727)

I found The Forty Days

of Musa Dagh – which I had never before read in any form -- amazing in a

number of ways. I devoured the dense, nearly 900 page novel in just a few days,

unable to put it down. I read the newly-published translation of Franz Werfel’s

1933 masterpiece, which includes about 25% more narrative than the previous

English version.

I should write a long review, including some research into

Werfel himself, but right now I only want to cover a few generalities about the

wonderful quality of the book.

First, I admired Werfel’s research into the 1915 massacre of

Armenians by the Turks. I think the history of these events was already being

suppressed by the late 1920s when Werfel began writing. His description of the

ragged, starving, perishing Armenian masses of men, women, and children from

the village of Zeitun was vivid. His descriptions of the Turkish authorities

and their rationale for the genocide (not yet given a name) were overwhelming.

The day-by-day description of the people of seven Armenian

villages near the Syrian coast who hid in the woods on the mountain Musa Dagh and

resisted the deportation to nowhere being inflicted by the Turks is powerfully

drawn. Each episode is based on true stories, particularly the survival of a

few thousand villagers on Musa Dagh and their rescue by French troop ships.

Werfel maintained a remarkable balance between descriptions

of collective suffering and of individual agony, so that the reader’s

consciousness is drawn in both directions. He occasionally mentions acts of

mercy by non-Armenians, but clearly shows that the moral bankruptcy of the

Turkish leaders (quite a few directly taken from history) corrupted the common

people, who are mostly depicted as looting and then resettling the villages

whose inhabitants have been forced out. Also corrupted: the military, civil,

and police authorities who directly deprived the Armenians of life and

property.

On the political side, I kept thinking: how could Werfel

write a Holocaust analogy before the Holocaust began? But I know the tragic

answer: he was trying to warn of the terrible future that somehow he saw so

clearly. Although he clearly admires the German Pastor Johannes Lepsius, another

of the historical characters depicted in the book, he had no illusions about

the meaning of the events to the mainstream German observers. While Lepsius

begs everyone who will listen to act to save the Armenians, almost no one will

listen to him; what aid he musters is too little too late. My very sad reaction

to Werfel’s attempted warning was that the main learners who took a lesson from

the massacre of the Armenians were the Nazis, not the humanitarians and not any

future victims.

On the novelistic side, I was also impressed by the author’s

choice of central characters, the French-educated Gabriel Bagradian. While the

history is powerful, I thin Werfel keeps the reader’s attention through the

depiction of Bagradian, his family, his determination to save his fellow

Armenians, and his close relationships. Bagradian’s conflicts between his

self-interest and his loyalty to his people, his developing identity from

identification with France and Europe to embracing of an Armenian identity, his

developing leadership in military and political affairs, and his tragic ending

create a perfect story against which Werfel presents the historical themes.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Mo Yan: The Garlic Ballads

I don’t understand China, but I decided to read The Garlic Ballads by this year’s

Nobelist in Literature, Mo Yan. I don’t understand the book any more than anything else about China. I can

follow the narrative, which is not in chronological order, but still not too complicated -- I just find the culture to be a challenge.

At the beginning of each chapter of The Garlic Ballads, we hear a few lines about garlic and politics, sung by a blind street singer named Zhang Kou. At the beginning:

At the beginning of each chapter of The Garlic Ballads, we hear a few lines about garlic and politics, sung by a blind street singer named Zhang Kou. At the beginning:

“Pray listen, my fellow villagers, to Zhang Kou’s tale of the mortal world and Paradise!

The nation’s founder, Emperor Liu of the Great Han,

Comanded citizens of our country to plant garlic for tribute…” (p. 1)

Who is Emperor Liu? I don’t know. Why garlic? We’ll find

out.

After a few lines of ballad starting each chapter, the

author slowly introduces a number of characters: dirt farmers in the village,

the poor and mistreated of China. They have planted garlic for the 1987 harvest

because it was selling for a lot of money – and because the planners told them

to. They are very poor. They complain all the time because of rapidly rising

prices of the things they need, such as pork and fertilizer for their garlic

fields. The peasant women even have to stand in line at the birthing center.

They constantly have to bribe the officials, who live much better than they do.

When it’s time to sell the garlic, the market collapses and

the farmers are left worse off than ever. Communist ideals of earlier days have

been betrayed as this new free enterprise enables whole new abusive situations

under the onus of bureaucracy. I think that this life doesn’t make sense to the

characters, and that’s a reason why it doesn’t make sense to me.

The first chapter tells of the arrest of one of these

farmers, Gao Yang, who seems to have no idea what crime he was being accused

of. Soon we meet another character named Gao Ma, who is also accused of a crime

– starting a riot at the local city hall. A third arrestee, who appears

somewhat later, is a woman of the village with a complicated relationship to

the others. The chapters bob and weave back and forth between the horrible

conditions in their jail cells, the filth, the lice, the smells, the abusive

fellow prisoners. We follow the prisoners’ memories of their lives, from the

time their fellow elementary school students mistreated them, through the

recent garlic debacle, and up to the time of their arrest.

Garlic is everywhere. Green shoots in the fields. Piled in the

farmers’ carts pulled by cow or donkey. In everything the farmers eat.

Overflowing the warehouses. Confiscated in shakedowns by petty officials.

Rotting in the street. An ingredient in many very unappetizing meals. Garlic

everywhere! The crop should have sold for lots of money. As the blind poet said,

“Sing of the brilliant Party Central Committee… Elders and brothers, get rich on garlic, remake yourselves!” (p. 205)

Food is one of the principal elements in the characters’

lives. Most of the time they eat coarse flatbread “hard and resistant as a

frozen rag.” In jail, one prisoner receives a bowl of noodle soup to make

others jealous, so they will abuse him – their normal ration is “one steamed

bun and a ladleful of soup.” (p. 87) The best meal in book is for a prisoner on

death row -- a last dinner of fatty pork, potatoes, wafer cakes fried on a

griddle and stuffed with green onions, and bean paste. (p. 247) Prison buns are

made from stale mildewed flour with a few vegetables – and garlic, “raw, cold

garlic,” “cold garlic broth” (pp. 79, 123)

Sometimes I felt as if I was reading an even grimmer version

of the “laughter through tears” style of Yiddish writers like Sholem Aleichem,

whose characters endured similar mistreatment -- though not really as degrading.

Reviewers have compared Mo Yan to Dickens, to Faulkner, or to South American

Magical Realists. Hmmm.

Comedy or tragedy? There’s a comic scene when Gao Ma attempts

to take a bride whose family had promised her elsewhere. But her tragic suicide

is in no way amusing. The failure to sell garlic involves some comic scenes.

But as the discouraged farmers, who had waited in a line of “farmers, trucks,

oxcarts, horsecarts, tractors, bicycles, even motorbikes” (p. 130), dragged

their garlic back home, one dies a tragic death when struck by a drunken

official driving an unlicensed car. The riot in government offices is somewhat

comic. I guess.

Jail time is too humiliating to be funny, as are lives of

mistreatment in memories; one charater says “dogs are better off than we are.

People feed them when they’re hungry, and as a last resort, they can survive on

human waste.” (p. 124) Finally, one accused prisoner stands up to the judges at

his trial, and a seemingly true voice of a noble soldier pleads for a better

society.

The epigraph to the entire novel is attibuted to Joseph

Stalin, “Novelists are so concerned with ‘man’s fate’ that they tend to lose

sight of their own fate. Therein lies their tragedy.” I say attributed, since

the only google hits for the quote are in articles about The Garlic Ballads, not about Stalin. I don’t understand this book.Sunday, October 14, 2012

School Lunch

School lunches are much in the news this fall, as recently-enacted nutritional standards are mandating changes. The public schools in St. Paul, Minnesota, have been experimenting with new programs for a few years, so I was very pleased to receive an invitation to have lunch at the Horace Mann Elementary School barbecue while visiting Miriam and Alice this week. I ate with Alice and several of her friends.

"Sometimes they have completely gross foods," says Alice, "but others are the best. I like the veggie pizza, but the chicken teriyaki and other meat items are gross."

As is evident in the photo, there are lots of vegetables -- and the classroom teachers discussed this with the children earlier in the year. Each child is required to try some veggies, which at least on the special family barbecue day were served on a sort of buffet in the cafeteria (which is also the gymnasium), after the line where the cafeteria ladies put the hot dog and baked beans on our foam trays. I gathered that there used to be things like chips on the menu which have disappeared this year.

The hot dog came on a whole-grain bun, baked in the central food prep kitchen according to the various articles I read earlier this fall. Alice ate the bun but not the hot dog. The children separate the food from the foam trays after lunch, and the edible rejects go to feed pigs at a special farm.

The "breakfast cookie" had lots of healthy ingredients, but didn't taste bad -- a tiny bit salty, I thought. Beverage choices: milk or chocolate milk. I doubt that I've tasted chocolate milk since I was eating in school cafeterias myself -- this was not as sweet and creamy as the chocolate milk of my childhood, if my memory serves.

During lunch Alice and her friends normally play a game called "Hello, Bob." Someone starts by saying, "Hello, Bob. Say hello to Bob, Bob." The response is to say "Hello Bob," and turn to the next person and say the same thing. Everyone has to talk in a sort of British or Australian accent. Eventually they also say "Hello, Sheila," or "Hello, Steve Owen." Hard to describe this one, but a couple of other visiting fathers and mothers and I played along with the group.

"The school lunches are better than our old school lunches," says Miriam, who ate lunch with Evelyn and Lenny and some of her friends elsewhere in the lunch room. "But home made lunches are still better."

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Disorder as art in food photos

Not all food in art is perfect, as many Renaissance artists illustrated. In a current New York times article, photographer Laura Letinsky's work demonstrates the same principles. Both in her fine-art work and in her magazine illustrations she uses chaotic or at least very informal tables with the remains of a meal, a cup of tea, or a party.

According to the article:

"Dirty spoons, empty cantaloupe rinds, half-eaten lollipops and clumsily cut slices of bread are her trade. Her pieces, she said, explore 'the problem of the illusion of perfection.' ...

"Even Brides, a magazine that would presumably want to present images of serenity and order, ran in its July issue Ms. Letinsky’s photographs of table settings. In these pictures macaroons are half-eaten and abandoned. Teacups and bowls are askew, and party organizers have hastily tied together a mishmash of silverware. The associates who work with Ms. Letinsky on these magazine pieces seem tickled by her chaos."

Several slick food magazines have used her work -- but evidently there are still quite a few editors who think their readers aren't ready for such realism.

Tuesday, October 09, 2012

McDonald's Everywhere

Here: a wonderful illustrated round-up of McDonald's adaptations in other lands. I would love to try some of them, like the Moroccan McArabia -- a cumin-spiced flatbread chicken sandwich (the article says it's beef but the photo is titled chicken).

Or like the Turkish Kofteburger -- "the McDonaldization of kofte, a type of Turkish kebab made with mint and parsley." The photo looks pretty much like any McD's sandwich, but it includes a lot of parsley. In China there's even a special McD's for the Chinese New Year.

Saturday, October 06, 2012

What makes us human?

Very early hominids at some point learned to eat cooked food. This allowed evolution of "smaller guts, bigger brains, bigger bodies, and reduced body hair; more running; more hunting; longer lives; calmer temperaments; and a new emphasis on bonding between females and males. The softness of their cooked plant foods selected for smaller teeth, the protection fire provided at night enabled them to sleep on the ground and lose their climbing ability, and females likely began cooking for male, whose time was increasingly free to search for more meat and honey. .... one lucky group became Homo erectus -- and humanity began."

So ends the last chapter of Catching Fire: How Cooking Made us Human by Richard Wrangham (quotes from p. 194). The book is a wide-ranging compendium of the scientific evidence for each of the points made in this summary -- not a collection of speculations or just-so stories, but hard research-supported data. The evidence is overwhelming. And as a bonus, in the Epilogue, he observes some of the consequences of his conclusions as they apply to the modern tendency towards obesity, and has a really interesting overview of the deficits in currently available nutrition and calorie information.

Wrangham's study of evolution and of the chemistry, physics, and nutritional value of cooked vs. raw foods has rapidly become a classic. From the time of first reviews, which I read shortly after its publication in 2009, until now, when it's referenced by a wide variety works on food and evolution, I've been meaning to read it. Finally I have done so.

So ends the last chapter of Catching Fire: How Cooking Made us Human by Richard Wrangham (quotes from p. 194). The book is a wide-ranging compendium of the scientific evidence for each of the points made in this summary -- not a collection of speculations or just-so stories, but hard research-supported data. The evidence is overwhelming. And as a bonus, in the Epilogue, he observes some of the consequences of his conclusions as they apply to the modern tendency towards obesity, and has a really interesting overview of the deficits in currently available nutrition and calorie information.

Wrangham's study of evolution and of the chemistry, physics, and nutritional value of cooked vs. raw foods has rapidly become a classic. From the time of first reviews, which I read shortly after its publication in 2009, until now, when it's referenced by a wide variety works on food and evolution, I've been meaning to read it. Finally I have done so.

Wednesday, October 03, 2012

A Judgement of Foodies

"Let's start the foodie backlash" by Steven Poole, a very long and ranting article in The Guardian, condemns many things about the modern interest in food, in food TV, in exotic and excessively innovative cooking experiments, and in a wide variety of what he sees as a new version of gluttony.

Straight out of primitive Christianity: medieval gluttony, he says, "wasn't necessarily a matter of eating too much; it was the problem of being excessively interested in food, whatever one's actual intake of it." He cites definitions by various authors:

Straight out of primitive Christianity: medieval gluttony, he says, "wasn't necessarily a matter of eating too much; it was the problem of being excessively interested in food, whatever one's actual intake of it." He cites definitions by various authors:

- Francine Prose -- gluttony is the "inordinate desire" for food, which makes us "depart from the path of reason."

- Spenser's The Faerie Queene -- "loathsome Gluttony ... Whose mind in meat and drinke was drowned so."

- Thomas Aquinas and Pope Gregory -- "gluttony can be committed in five different ways, among which are seeking more 'sumptuous foods' or wanting foods that are 'prepared more meticulously.'"

Wow!

Poole criticizes those who claim their love of food is spiritual; he condemns those who title their cookbooks Bibles; he sneers at those who say that their fine cooking is an art form. He delves into the history of words like "foodie" and "foodist," finding nothing to like I would say.

He summarizes his indictment:

Poole criticizes those who claim their love of food is spiritual; he condemns those who title their cookbooks Bibles; he sneers at those who say that their fine cooking is an art form. He delves into the history of words like "foodie" and "foodist," finding nothing to like I would say.

He summarizes his indictment:

Western industrial civilisation is eating itself stupid. We are living in the Age of Food. Cookery programmes bloat the television schedules, cookbooks strain the bookshop tables, celebrity chefs hawk their own brands of weird mince pies (Heston Blumenthal) or bronze-moulded pasta (Jamie Oliver) in the supermarkets, and cooks in super-expensive restaurants from Chicago to Copenhagen are the subject of hagiographic profiles in serious magazines and newspapers.Normal people would normally hate the foods they are made to love, he says. They are being psyched out by hype and fancy menu descriptions:

In an experiment, two psychologists gave different groups of people Heston Blumenthal's "Crab Ice-Cream" while describing it differently: one group was told it was about to eat a "savoury mousse", the other was expecting "ice-cream". The people given savoury mousse liked it, but the people thinking they were eating ice-cream found it "digusting" and even "the most unpleasant food they had ever tasted". The psychologists add that most food tastes "blander" without the "expectation of flavour caused by the visual appearance or verbal description of what is going to be eaten".I have my suspicions of the foodie trends that reach my little town Ann Arbor in attenuated and rather absurd (and unappetizing) ways, but I'm overawed by the vigor of the charges in this screed!

Sunday, September 23, 2012

Artichoke ice cream and other surprises

In the 18th century, ice cream was a novelty. Not new -- even the Romans had frozen desserts, and the transition to ice cream was gradual. It's another thing Marco Polo might have seen in China (but he didn't seem to have mentioned it). Books about ice cream were definitely new in the 18th century, though, and they offered a variety of flavors that would shame modern chefs who think of themselves as so ingenious. "Almost from the beginning, confectioners have pushed the ice cream envelope," writes Jeri Quinzio in her book Sugar and Snow: A History of Ice Cream Making. While her book includes many other subjects, I found her descriptions of ice cream flavors from the past to be the most fascinating part.

Artichoke ice cream -- neige d'artichaux in the original -- seems to me one of the most exotic. A French chef made it from "pistachios and candied orange, along with artichokes, and quite probably the finished product tasted less like artichokes than like pistachios and oranges," she says. (p. 39)

Another ice cream maker in France used truffles -- the fungus kind, not the chocolate kind. Vanilla at the time, however, was not yet a commonly used flavor -- favorites of the time included fruits, flowers, and spices like cinnamon, cloves, anise, saffron. Quinzio cites an author from that period who said no vegetable existed that couldn't be turned into ice cream. Slightly later flavors were pomegranate, jasmine, fennel with lemon, and nougat candy. Or a combination of cinnamon, lemon peel, and bay leaf. (p. 53, 142)

Parmesan cheese flavored ice cream is mentioned twice in Sugar and Snow. An author named Frederick Nutt mentioned it in a work called The Complete Confectioner in England in the late 18th or early 19th century. When talking of famous chefs of the late 20th century, Quinzio mentions miniature cornets filled with salmon tartare and crème fraîche but looking like ice cream cones -- part of a trend that includes desserts with new flavors that the chefs of the 18th century "would have recognized, such as Parmesan, artichoke, and truffle." (p. 207)

Even the creation of ice-cream-like savory dishes is not new. The Virginia House-Wife by Mary Randolph in 1824 had many recipes for dessert ices, but among them was "frozen oyster cream" which was oyster soup, strained and frozen; Quinzio says that Randolph gives no serving suggestion or explanation of this recipe. Similarly, she cites Fanny Farmer's Boston Cooking-School Cook Book's recipe for Clam Frappé: the liquid from steamed clams frozen "to a mush." Quisno gives the entire recipe for a Cucumber Sorbet, which actually sounds pretty refreshing to me. She also mentions rye-bread and brown-bread flavored ice creams. (p. 59, 79, 143, 151)

I enjoyed the historic material, for example, about the invention of the ice cream cone, which did not originate at the St.Louis World's Fair/Louisiana Exposition in 1904, but was the first place that made street food from what had been a fancy, table-served dish. I was amused to hear of one "bombe" made of ice cream that was really supposed to remind people of anarchists, and of Seabees creating an improvised ice cream maker from airplane parts and Japanese shell cases on a Pacific Island in World War II (p. 71 & 195). I was delighted to learn more about marshmallows -- how they were melted and used for frozen desserts in early home freezers (my mother did this -- her specialty was coffee mallow, which didn't work when she got a freezer that maintained a truly cold temperature). And how Rocky Road ice cream with marshmallows in it was supposedly invented by William Dreyer in Oakland, California, in 1929. But I most loved the lists of exotic flavors.

Artichoke ice cream -- neige d'artichaux in the original -- seems to me one of the most exotic. A French chef made it from "pistachios and candied orange, along with artichokes, and quite probably the finished product tasted less like artichokes than like pistachios and oranges," she says. (p. 39)

Another ice cream maker in France used truffles -- the fungus kind, not the chocolate kind. Vanilla at the time, however, was not yet a commonly used flavor -- favorites of the time included fruits, flowers, and spices like cinnamon, cloves, anise, saffron. Quinzio cites an author from that period who said no vegetable existed that couldn't be turned into ice cream. Slightly later flavors were pomegranate, jasmine, fennel with lemon, and nougat candy. Or a combination of cinnamon, lemon peel, and bay leaf. (p. 53, 142)

Parmesan cheese flavored ice cream is mentioned twice in Sugar and Snow. An author named Frederick Nutt mentioned it in a work called The Complete Confectioner in England in the late 18th or early 19th century. When talking of famous chefs of the late 20th century, Quinzio mentions miniature cornets filled with salmon tartare and crème fraîche but looking like ice cream cones -- part of a trend that includes desserts with new flavors that the chefs of the 18th century "would have recognized, such as Parmesan, artichoke, and truffle." (p. 207)

Even the creation of ice-cream-like savory dishes is not new. The Virginia House-Wife by Mary Randolph in 1824 had many recipes for dessert ices, but among them was "frozen oyster cream" which was oyster soup, strained and frozen; Quinzio says that Randolph gives no serving suggestion or explanation of this recipe. Similarly, she cites Fanny Farmer's Boston Cooking-School Cook Book's recipe for Clam Frappé: the liquid from steamed clams frozen "to a mush." Quisno gives the entire recipe for a Cucumber Sorbet, which actually sounds pretty refreshing to me. She also mentions rye-bread and brown-bread flavored ice creams. (p. 59, 79, 143, 151)

I enjoyed the historic material, for example, about the invention of the ice cream cone, which did not originate at the St.Louis World's Fair/Louisiana Exposition in 1904, but was the first place that made street food from what had been a fancy, table-served dish. I was amused to hear of one "bombe" made of ice cream that was really supposed to remind people of anarchists, and of Seabees creating an improvised ice cream maker from airplane parts and Japanese shell cases on a Pacific Island in World War II (p. 71 & 195). I was delighted to learn more about marshmallows -- how they were melted and used for frozen desserts in early home freezers (my mother did this -- her specialty was coffee mallow, which didn't work when she got a freezer that maintained a truly cold temperature). And how Rocky Road ice cream with marshmallows in it was supposedly invented by William Dreyer in Oakland, California, in 1929. But I most loved the lists of exotic flavors.

Friday, September 21, 2012

Sunkist Oranges and Birds Eye Peas

Wednesday night I attended the regular meeting of the Culinary Book Club that I belong to. We read Birdseye by Mark Kurlansky, a biography of Clarence Birdseye. The subject of the bio developed processes for frozen food technology: how to freeze it quickly with a variety of huge devices, package it with new materials that survived freezing, and keep it frozen -- besides industrial freezing machines, he also developed less expensive refrigeration units for shipping and storing it in markets. Birdseye began with his own business, and then sold his idea to a company that could invest more in the project than he could raise.

That company became General Foods, and Birdseye, whose name became synonymous with frozen food (especially peas) ran a food lab for them for a number of years. I found him interesting both for having changed American food, including ideas for distribution to grocers and inventing freezers where they could store the foods he froze, and for his amazingly adventurous attitude towards eating and trying exotic foods and small game animals that most of his peers would not have accepted.

Birdseye also invented a variety of other very practical things such as a reflector lightbulb. He traveled to a number of spots in the New World, like Labrador -- where he got the idea for frozen food, which in its time was a big improvement over canning. The discussion was fun; some of us talked about our memories of refrigerators, ice men, ice boxes, and home freezers. One woman described how she received an upright freezer for a wedding present when she had almost no money, but her family considered it essential.

This week also, I read another book, Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden by Douglas Cazaux Sackman. It's a more academic study but very well-written. It details the history of the orange industry in California -- and it was really an industry, allied with the Southern Pacific Railroad. Beginning around the turn of the 20th century, orange-grove owners figured out how to mass-produce uniform fruits, which became a commodity. The growers' association united the rich owners of large groves, who marketed collectively under the still-well-known name Sunkist.

The industry pioneered ways of advertising to create demand, including medical studies commissioned to show how important oranges were to health. Sound familiar? It was done again, perhaps more dishonestly, this decade by pomegranate producers in California, though the author doesn't mention that.

The book answers one question I had wondered about in the past: when did oranges become common rather than a special treat to be eaten only at Christmas. I loved the description of a Sunkist ad where a woman asks a small grocer for oranges, and he says he stocks them only at Christmas -- but the point of the ad is that the bigger supermarkets, which were cooperating with the orange growers and railroads, were beginning to stock them all year. I believe this was in the 1920s, by which time piles of perfect oranges were on display in markets throughout the land, and people were becoming convinced to drink OJ for breakfast daily and feed it to babies.

Further, the book documents how mass orange-growing was an industry with political implications for labor and unions, use of pesticides and other poisons, immigration, racism, exploitation of land and workers by rich growers, water rights, and a number of other issues that started 100 years ago and haven't been resolved in America. One radical critic of the terrible labor practices and union-busting efforts referred to the oranges as Gunkist! The conflicts involved a number of very famous Americans and famous books like Grapes of Wrath of course, as well as a fascinating governor's race in which the author Upton Sinclair almost won on a very radical platform. (The growers and railroads used a negative campaign to defeat him in the last 6 weeks: makes me shudder!)

Most of the California groves have now been replaced by housing developments and urbanization; for example, Disneyland replaced orange groves. Both books are very very American stories that reveal interesting developments in American foodways.

The industry pioneered ways of advertising to create demand, including medical studies commissioned to show how important oranges were to health. Sound familiar? It was done again, perhaps more dishonestly, this decade by pomegranate producers in California, though the author doesn't mention that.

The book answers one question I had wondered about in the past: when did oranges become common rather than a special treat to be eaten only at Christmas. I loved the description of a Sunkist ad where a woman asks a small grocer for oranges, and he says he stocks them only at Christmas -- but the point of the ad is that the bigger supermarkets, which were cooperating with the orange growers and railroads, were beginning to stock them all year. I believe this was in the 1920s, by which time piles of perfect oranges were on display in markets throughout the land, and people were becoming convinced to drink OJ for breakfast daily and feed it to babies.

Further, the book documents how mass orange-growing was an industry with political implications for labor and unions, use of pesticides and other poisons, immigration, racism, exploitation of land and workers by rich growers, water rights, and a number of other issues that started 100 years ago and haven't been resolved in America. One radical critic of the terrible labor practices and union-busting efforts referred to the oranges as Gunkist! The conflicts involved a number of very famous Americans and famous books like Grapes of Wrath of course, as well as a fascinating governor's race in which the author Upton Sinclair almost won on a very radical platform. (The growers and railroads used a negative campaign to defeat him in the last 6 weeks: makes me shudder!)

Most of the California groves have now been replaced by housing developments and urbanization; for example, Disneyland replaced orange groves. Both books are very very American stories that reveal interesting developments in American foodways.

Labels:

Ann Arbor,

Culinary Book Club,

Mark Kurlansky,

Oranges,

Posted in 2012

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Marshmallows

On one of the delightful reruns of Julia Child shows, she and Jacques Pepin make a turkey dinner with all the traditional side dishes. As she heaps sweet potatoes into a serving dish, she says something like this to the audience, "These are plain mashed sweet potatoes, but you could make candied sweet potatoes with marshmallows. I love candied sweet potatoes."

Pepin says "I don't like marshmallows," and she answers, "Of course not, you're French."

I've been aware for ages that French people generally don't like marshmallows -- I've probably already mentioned somewhere in this blog how a French friend trying a toasted marshmallow said "It's like a jellyfish."

But here's the odd thing: the French invented marshmallows as we know them today, which in French are called guimauves. According to "It's a Marshmallow World," in Smithsonian: "The modern marshmallow confection is a mid-19th century French invention and was a cross between medicinal lozenge and bonbon."

Like the English word marshmallow, the French guimauve is the name of a marsh plant whose root produces a sticky substance. An extract of this substance was originally used to provide the unique texture of marshmallows -- sticky but firm, I guess you could say. Gelatine was soon substituted for the extract of plant roots, and for a long time, the classic marshmallow or guimauve was made by confectioners. I'm curious how its popularity grew in the US while obviously declining or maybe never taking off in France.

Use of the marshmallow plant (illustration at right from Wikipedia -- scientific name Althaea officinalis) has a long history. Smithsonian: "Greek physician Dioscorides advised that marshmallow extracts be used in treating wounds and inflammations. During the Renaissance, extracts from the plant’s roots and leaves were used for medicinal purposes, namely as an anti-inflamatory and soothing agent for sore throats." Wikipedia says that the Romans considered them a delicacy.

Today's New York Times Magazine article "Who Made that Marshmallow?" contains the most recent history of how marshmallows are made. The 1950s saw the development of industrial processes to "jet puff" the marshmallows (note the words "Jet Puffed" on the marshmallow bag in the top photo). An invention created a series of machines that forced a "marshmallow slurry through tubes, subjected it to blasts of gas at 200 pounds per square inch, extruded it into long tails and then cut it into bite-size chunks."

The traditional mixture of sugar, egg white, and gelatine required a long and labor-intensive treatment to produce marshmallows, though marshmallows appear to have been mass produced early in the 20th century, when products like Mallomars were introduced. A brief history of Smores says that camping was growing in popularity and the ingredients -- marshmallows, graham crackers, and chocolate bars -- were quite portable. I remember carefully packed boxes of Campfire marshmallows with two layers of around 10 marshmallows each, probably when they were not quite as speedily and cheaply produced.

So I wonder, what were the French doing in 1927 when the Girl Scout Handbook published the first recipe for S'Mores? In 1919 when "a booklet from the Barrett Company on Sweet Potato and Yams ... suggests adding marshmallows to candied yams"? (Referenced here) In 1913 when Nabisco made the first Mallomars? What about Whippets, moon pies, Peeps, and those jellyfish-like toasted marshmallows? I guess they were eating mousse au chocolate, grilling steaks, and maybe avoiding the yams as well as the candied part.

And the French still hand-make their marshmallows -- for a photo see this blog post.

Sunday, September 09, 2012

Manifold Cooking

At today's Old Car Festival in Greenfield Village, I learned about a cookbox that was made, back in the day, to fit over the exhaust manifold of a Ford Model T. You can see the metal box just behind the headlamp here:

At the demo in front of the reviewing stand the beautifully dressed passenger in the car got out, lifted the side of the hood (the Model T had a sort of fold-up hood on either side of the engine), and spooned up some soup to show the crowd -- note the spoon in the Flapper's hand:

Cooking under the hood of a Model T involved understanding the very high heat that could result from the operation of the engine, and gauging how far to go and at what speed you should travel in order to get the best result from your recipe. The announcer noted that in fact, some recipes suggested going up hills to increase the temperature. Evidently this was a popular part of the entertaining new sport of driving around in a Model T around 100 years or so ago. The car in the photo is a 1927 model.

Here is a sample of a couple of modern recipes for this cooker, from a website I found (maybe it's even the website of the people in the photo):

At the demo in front of the reviewing stand the beautifully dressed passenger in the car got out, lifted the side of the hood (the Model T had a sort of fold-up hood on either side of the engine), and spooned up some soup to show the crowd -- note the spoon in the Flapper's hand:

Cooking under the hood of a Model T involved understanding the very high heat that could result from the operation of the engine, and gauging how far to go and at what speed you should travel in order to get the best result from your recipe. The announcer noted that in fact, some recipes suggested going up hills to increase the temperature. Evidently this was a popular part of the entertaining new sport of driving around in a Model T around 100 years or so ago. The car in the photo is a 1927 model.

Here is a sample of a couple of modern recipes for this cooker, from a website I found (maybe it's even the website of the people in the photo):

Rhubarb Ice cream topping

Line the cooker with foil ..., slice fresh rhubarb into small pieces, add a handful or two of sugar, drive to an ice cream store at least 20 miles away, buy a dish of ice cream, put the topping on it and enjoy the best topping yet cooked on a Model T manifold.

Meat LoafHere is another view of the car at the reviewing stand and the Flapper, spoon still in hand:

(this is the most popular recipe we have made on the manifold)

Note this is also known as ‘Greasy Fan Belt Goulash’

Mix one pound of lean ground beef with one package of frozen Potatoes O’Brian, one package of frozen Mexicorn and a jar of Salsa (you choose mild, medium, hot, or acetylene torch-like). I always dump all the ingredients in a big zip lock bag to mix them…..since my hands are always greasy.

Anyway, mix well and then dump it all into a big piece of wide Aluminum foil and wrap it into a loaf that will fit into the cooker. Drive about 40 miles or so and it will be done.

This recipe is so good that dogs and people will follow you.

Wednesday, September 05, 2012

Food in Poetry

I often write about food in novels or other books I have read. I have just found a Poetry Magazine collection of poems that feature food. Other than the famous one about plums by William Carlos Williams ("This is just to say"), or the Ogden Nash short poems published in the book depicted at right like the one about the parsnip, I couldn't easily think of any food poems. I'm not that much of a poetry reader, as it happens; however, several of these poems appealed to me.

Being a fan of Gertrude Stein, I enjoyed the poem titled "Christian Bérard." I already know quite a bit about what Gertrude Stein liked to eat, because of the Alice B. Toklas Cookbook. Here are the first lines of the poem:

BY GERTRUDE STEIN

Eating is her subject.

While eating is her subject.

Where eating is her subject.

Withdraw whether it is eating which is her subject. Literally while she ate eating is her subject. Afterwards too and in between. This is an introduction to what she ate.

She ate a pigeon and a soufflé.

That was on one day.

She ate a thin ham and its sauce.

That was on another day.

She ate desserts.

That had been on one day.

She had fish grouse and little cakes that was before that day.

She had breaded veal and grapes that was on that day.

After that she ate every day.

Very little but very good.

She ate very well that day.

What is the difference between steaming and roasting, she ate it cold because of Saturday.

Remembering potatoes because of preparation for part of the day.

There is a difference in preparation of cray-fish which makes a change in their fish for instance.

What was it besides bread.

Why is eating her subject. There are reasons why eating is her subject.

...

Two other poems that I liked are by poets I was previously unfamiliar with: Paul Blackburn and Victor Hernandez Cruz. And there are so many more!

The beginnings of these poems:

BY PAUL BLACKBURN

Slowly and with persistence

he eats away at the big steak,

gobbles up the asparagus, its

butter & salt & root taste,

drinks at a glass of red wine, and carefully

taking his time, mops up

the gravy with bread—

The top of the café filtre is

copper, passively shines back, & between

mouthfuls of steak, sips of wine,

he remembers

at intervals to

with the flat of his hand

the top removed,

bang

at the apparatus,

create the suction that

the water will

fall through

more quickly

Across the tiles of the floor, the

cat comes to the table : again.

“I’ve already given you one piece of steak,

what do you want from me now? Love?”

...

BY VICTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ

Next to white rice

it looks like coral

sitting next to snow

Hills of starch

border

The burnt sienna

of irony

Azusenas being chased by

the terra cotta feathers

of a rooster

...

Being a fan of Gertrude Stein, I enjoyed the poem titled "Christian Bérard." I already know quite a bit about what Gertrude Stein liked to eat, because of the Alice B. Toklas Cookbook. Here are the first lines of the poem:

Christian Bérard

BY GERTRUDE STEIN

Eating is her subject.

While eating is her subject.

Where eating is her subject.

Withdraw whether it is eating which is her subject. Literally while she ate eating is her subject. Afterwards too and in between. This is an introduction to what she ate.

She ate a pigeon and a soufflé.

That was on one day.

She ate a thin ham and its sauce.

That was on another day.

She ate desserts.

That had been on one day.

She had fish grouse and little cakes that was before that day.

She had breaded veal and grapes that was on that day.

After that she ate every day.

Very little but very good.

She ate very well that day.

What is the difference between steaming and roasting, she ate it cold because of Saturday.

Remembering potatoes because of preparation for part of the day.

There is a difference in preparation of cray-fish which makes a change in their fish for instance.

What was it besides bread.

Why is eating her subject. There are reasons why eating is her subject.

...

Two other poems that I liked are by poets I was previously unfamiliar with: Paul Blackburn and Victor Hernandez Cruz. And there are so many more!

The beginnings of these poems:

The Café Filtre

BY PAUL BLACKBURN

Slowly and with persistence

he eats away at the big steak,

gobbles up the asparagus, its

butter & salt & root taste,

drinks at a glass of red wine, and carefully

taking his time, mops up

the gravy with bread—

The top of the café filtre is

copper, passively shines back, & between

mouthfuls of steak, sips of wine,

he remembers

at intervals to

with the flat of his hand

the top removed,

bang

at the apparatus,

create the suction that

the water will

fall through

more quickly

Across the tiles of the floor, the

cat comes to the table : again.

“I’ve already given you one piece of steak,

what do you want from me now? Love?”

...

Red Beans

BY VICTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ

Next to white rice

it looks like coral

sitting next to snow

Hills of starch

border

The burnt sienna

of irony

Azusenas being chased by

the terra cotta feathers

of a rooster

...

Labels:

Food in Literature,

Gertrude Stein,

Posted in 2012

Tuesday, September 04, 2012

Tarte au Citron

My project: to master a recipe for French-style Tarte au Citron. Above: my first effort. The crust and sugared lemons on top were based on this: How to cook perfect tarte au citron. I used a Julia Child recipe for the filling. The crust, especially, needs work, but the result was quite delicious.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Patty-Pan Squash

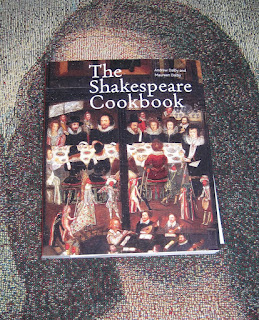

For dinner: stuffed little patty-pan squash. Inspired by the Shakespeare cookbook, I spiced the breadcrumb, onion, and insides-of-squash filling with fresh thyme (also from the market), nutmeg, lemon zest, and raisins. It wasn't a Shakespeare recipe, though, just an improvisation.

Ann Arbor: The Farmers Market

The farmers market here is a bit sad this year because so much of the tree fruit was destroyed by an early warming period in March followed by bad frosts last April. Moreover, the drought is serious; some farmers have been able to water their crops, but others are suffering.

I talked to one farmer who said that throughout July, he drove 5 miles to a city water supply and brought a 3000 gallon tank of water back to irrigate his tomatoes, peppers, and other field crops, supplementing his well. I have no idea of the cost tradeoffs or efforts this implies. In sum, the weather of all sorts, mostly bad, has also caused prices to increase.

This was my first trip to the market for the year. The plums, peaches, tomatoes, peppers, and herbs I bought were delicious for lunch; we'll also be eating eggplant, patty-pan squash, early apples, and a few other items this week.

Friday, August 24, 2012

What did Shakespeare eat?

What did Shakespeare eat?

Definitive answers here: The Shakespeare Cookbook by Andrew Dalby and Maureen Dalby, published by the British Museum Press this year. Andrew Dalby is a culinary historian, so this is a work of scholarship, using contemporary cookbooks and dietary advice books that were in print during Shakespeare's lifetime. I had no idea how many such works existed!

Another surprise: many recipes are simple and close to modern cooking. For example, chicken fricassee described on page 54 is almost exactly the way I sometimes use up leftover chicken, though the modern version often includes pimentos (a variety of capsicum peppers, which Dalby says hadn't reached England from the New World yet) and the Shakespeare-era version uses the spice mace, which isn't on my spice shelf.

A variety of pies of all sizes combine meat, fruit, suet, and spice into a preparation that predates our mince pies. The small ones are called "chewets" and contain saffron and ground ginger along with cooked meat. If I could find suet, I would be interested to try pies or chewets, as I have always liked that funny packaged mincemeat that is featured at Christmas and Thanksgiving, and I would like to meet its ancestor. (If I could find a swan, there's another recipe in the book I might try too.)

Similarly there are recipes for a sort of meatball including meat-egg-dried fruit and flavored with mace. Large ones were called Farts, small ones were called Fysts. I definitely plan to try these, as the modernized recipe doesn't require suet at all. And the name is so amusing! Dalby doesn't offer any word history on this. Although there are many references on the Web to the original recipe, a quick look didn't offer me any insight into why this word meant little meatballs in Elizabethan times.

The explanation of what the word "cake" meant to Shakespeare is very interesting. "A cake, to Shakespeare, was a concept that overlapped with the modern English cake but didn't coincide with it." (page 70)

So, the authors point out, cakes could sweet or savory in the famous line

"Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, that there shall be no more cakes and ale?"The word cake could refer to a loaf cake, a tea-cake, or a waffle. It could mean a biscuit. (I think this is the British biscuit, which in America we call a cookie -- the problem of terminology didn't stop in Shakespeare's time.) The book's cake recipe is for Barm Brak, made from white-bread dough, sugar, lard, eggs, raisins, and sweet spices.

Every section of the book has a discussion of a food reference in a particular Shakespeare play, with elaborations from the literature of Shakespeare's contemporaries as well as contemporary food sources. Almost every page includes an illustration, also contemporary to Shakespeare. And every section offers a wide range of interesting references and information, as well as at least one recipe quoted directly from the sources and then a modernized version. A fantastic book, for which I'm grateful to my friend Sheila!

Monday, August 20, 2012

Julia Child Recipes

More spinoff from thinking about Julia Child's 100th birthday ...

August 17: Champignons a la Grecque, served with tomato, cucumber, and cilantro.

Tonight: a clafoutis made with huge black cherries. I think I last made this in 1965, though I suspect I have made clafoutis with other fruit once or twice in the intervening years. My guest in 1965 quipped, "What about clafou-coffee?"

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Happy Birthday Julia Child and Evelyn

Julia Child would be 100 years old today -- as every food blogger and food writer knows. I first encountered her work and TV show in the fall of 1964, when I was newly married and learning to cook. Marcy, the secretary of the office where I was working was a member of Book of the Month Club, and purchased Mastering the Art of French Cooking for me at a reduced price. I loved it immediately!

In gratitude, we invited Marcy to dinner, though in fact we didn't have much in common with her. I made the recipe on page 246: "Roast squab Chickens with Chicken Liver Canapes and Mushrooms" -- I used Rock Cornish Hens. I have never made that recipe again, though I've tried dozens of others in that book. Why I remember that one, I can't imagine. I served it on a beautiful Danish Modern wood tray that had been a wedding present. Forever after it faintly smelled of liver.

Over time, I've memorized many of the recipes from Mastering the Art of French Cooking, and now make them without looking. A few of these favorites: onion soup, carbonnades a la Flamande, casserole roasted veal, gratin Dauphinoise, salade Nicoise. I once roasted a goose according to her recipe (memorable, but it's hard to find another goose), and once made Riz a l'Imperatrice (disappointing). I made clafoutis a few times. I use her recipes for crepes, ratatouille, daube de Provence, and chicken with tarragon, and quite a few others. Despite my love of artichokes, I don't recall having tried her method of trimming them down to the artichoke bottoms and then stuffing them. And I admit that I've never had the patience to try the most challenging desserts, those with puff pastry.

Over the years, I have acquired other Julia Child books, beginning with the second volume of Mastering..., which was published a few years later. Compared to my original copy of Volume I, full of stains, splashes, and dog-ears, my Volume II is pristine. I'm not sure I've ever made a single recipe from it, though Lenny did make the French bread recipe for a while. It's full of things I would be afraid to try, like roast suckling pig.

Julia Child & Company, published in 1978, turned out to be a real favorite. My copy is full of notes about when I cooked various dishes or even whole meals. For example, the "Indoor Outdoor Barbecue" gave us the idea of cooking a butterflied leg of lamb on the barbecue. It's fantastic -- we have done it often. My handwritten notes on page 193 record that I made the entire dinner on May 6, 1984 (including the Topinambours, or Jerusalem artichokes), and repeated all or part of it in 1992, 2004, and 2010. Here's the photo of that meal from the book:

I have loved all her books that I own -- shown at the top of this post. The one I bought most recently was My Life In France, her wonderful autobiography. And I have also enjoyed her kitchen in the Smithsonian, which I wrote up here.

Happy Birthday, Julia. And also happy birthday Evelyn, who shares her birthday.

Monday, August 13, 2012

Salad Number 4

Favorite salad flavor for Miriam and Alice: the spice blend Maggi Number 4, available only in Germany. They unselfishly gave me a jar of it, which you can see I have all ready to make a salad. Last night, I mixed some of this blend with olive oil and red-wine vinegar and sprinkled it on skewers of mushrooms, onions, and red/orange bell peppers. I kept this separate from meat, so after cooking we used the remaining marinade as a dressing for the vegetables. It's really a wonderful flavor blend.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)