|

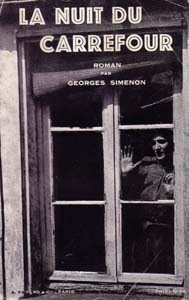

| Renoir Self-Portrait, 1875. |

Susan Vreeland's novel

Luncheon of the Boating Party is a fictional account of how Pierre-Auguste Renoir created his very famous and much-loved painting of the same name. Fourteen faces appear in the painting of a beautiful luncheon outdoors at a restaurant along the Seine River in what was then the more rural part of Paris (now enveloped in the much larger city). All these figures (except one mystery face) have been identified: they were friends and acquaintances of Renoir. The painter did not include a self-portrait in this masterpiece, but I have included one that he painted in 1875, a few years before he painted the boating party.

Vreeland has woven a complex and highly enjoyable story of his relationships with this group, telling much about who they were and how they lived. Fortunately,

a Wikipedia article has called them out with thumbnails of their faces from the painting, and I've selected a few favorites out of the fourteen faces in the painting, which I'll introduce to you here, while trying to give an idea of what's in the book:

Louise-Alphonsine Fournaise

Louise-Alphonsine Fournaise – the girl leaning on the railing – was the daughter of the family that owned the water-side restaurant where Renoir's luncheon – and much of the action of Vreeland's book – took place. She worked in the restaurant, helping her mother who was the cook and helping her father with the customers. She was a remarkably self-educated woman, who knew about art and who encouraged Renoir's difficult task of painting a huge multi-person portrait outdoors from life: a very complex endeavor.

We often see her in connection with the food served in the restaurant, for example,

"Alphonsine brought up a plate of green beans, fried potatoes, and grenouilles, frog legs sautéed with garlic and parsley, a common dish here because frogs in marshy areas jumped right into your hand." (p. 22).

"The main course was canard à la paysanne, braised duck garnished with carrots, turnips, onions, celery, bacon, and fried potatoes. Auguste didn’t know how he could sit still and eat. He was conscious only of the painting moving before his eyes. Conversations separated, blended, jumped from one topic to another. He didn’t follow them. Alphonsine brought out two large raspberry tarts. The light on her raised cheeks issued from within. She cut generous pieces, and lingered by the railing watching intently as each person took a bite. 'Did you make these?' Auguste asked. 'With a little help from the sun and rain.'" (p. 98).

"She was amused by her mother announcing the entrées as she and Maman set the platters on the table. 'Pâté maison and asperges d’Argenteuil en conserve. The best quality in France, grown less than five kilometers from here. 'Pretty as a picture, madame,' Charles said and helped himself to quite a few spears. 'I love asparagus so much I had Manet paint them for my dining room, as a hint to my cook to prepare them more often.'" (p. 158).

Aline Charigot

Aline Charigot – shown with her little dog – was a beautiful but uneducated and nearly illiterate young woman. She appears in Renoir's neighborhood when he stops for a coffee:

"La Crémerie de Camille was crowded with young women chatting over their café au lait before heading to work at milliners’ shops or dressmakers’ lofts or laundries. Auguste greeted Aline, a seamstress with a Burgundian accent and a creamy complexion, and Géraldine, a pork butcher’s assistant with a meaty fragrance but with a silk rosebud pinned to her gray frock." (p. 59).

Although Aline was not among the original subjects for the painting, once she's made part of it her importance becomes very obvious. Renoir begins to adore her and he has to convince her protective and untrusting mother to let her pose every Sunday at the boathouse.

Among other things, he tempts her with the fine meals they eat before each sitting for his painting:

“Every Sunday we have one of Mère Fournaise’s delicious meals. So far we’ve had canard à la paysanne with artichauts à la vinaigrette, poulet forestière with asperges d’Argenteuil en conserve, lapin en gibelotte, friture d’ablettes, de gardons et de goujons.' 'Mm. The duck must have been nice, but I’m sorry I missed the rabbit stew. It reminds me of home.' 'And for dessert, raspberry tarts and apple pastry.'" (p. 260).

At the end of the novel, one learns that soon after the painting was finished Aline began to live with Renoir. She married him after 10 years of living with him, and was the mother of his children.

Gustave Caillebotte was a very rich art collector, patron, and a highly original painter. He was very much a part of the boating party because he was also such an avid boat owner and boat racer. Part of the suspense – will Renoir be able to finish the painting? – is due to an upcoming boat race, which will require all the space on the restaurant terrace and thus disable Renoir's project. Caillebotte and his boats were very much involved in this race!

Caillebotte is famous today because he sponsored and subsidized the Impressionists while also painting in their style, and his collection and vision was critical in creating their long-term reputation. The circle included Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, and a few others.

Paul Lhôte was another associate who supported Renoir's project. One of his friends describes him:

“Paul Lhôte. A loose screw. Hungry for experiences. Reckless. A writer of articles and an amateur painter. He escapes his deadly conventional post at a shipping company by collecting unconventional adventures.” “Such as?” “Stowing away to South America on a packet ship. He lost his post for that escapade, so he immediately stowed away to Asia. On the isle of Jersey once he dared me to dive from a high cliff out over the rocks into furious waves. I thought he was crazy, but he did it, bare-assed, and came up laughing.” (p. 96).

Charles Ephrussi – the man with a top hat – was a wealthy art collector, and member of the circle of friends of Renoir and other Impressionists. The Ephrussi family is the subject of the book

The Hare With Amber Eyes, which I wrote about

here and

here.

One of the other members of the boating party characterized him thus:

“Charles Ephrussi, only son in a line of wealthy Russian bankers. Self-taught art connoisseur who buys and sells profitably. He’s tapped his ebony walking stick on the marble floors of every bank on rue Lafitte....Always razor-sharp creases in his trousers. Always dignified, the true flâneur strolling the boulevards, observing, then retreating to his plush study to write esoteric articles about his observations while snacking on caviar on toasted rye. But here, ha! A fish out of water. Wait till he discovers that he’ll be posing with two sweaty men in singlets, undergarments to him, one with the air of a carefree sailor, the other as brawny as a pirate.” (p. 155).

An additional description of Ephrussi's palatial home and art collection:

"Even Ephrussi’s outer office was redolent with sandalwood incense, the exotic aroma of his past as the heir of a corn-exporting dynasty in Odessa. Although Japanese prints adorned the anteroom, Auguste knew he’d find paintings by his friends in Ephrussi’s private office." (p. 142).

Vreeland's description discretely omits a fact about Charles Ephrussi that would have surely been quite important in Renoir's time: the Ephrussi family were not just Russian bankers, but were Jewish. Everyone would have been aware of this, as antisemitism was a critical factor in France during the final years of the 19th century. The closest Vreeland comes to mentioning Jewishness is in a quote about Pissarro, who was also Jewish: “Pissarro has no use for Degas because Edgar’s an anti-Semite." (p. 70).

How accurate was Vreeland's narrative?

Somehow Vreeland brings all fourteen characters together every Sunday when it's possible for Renoir to paint them, and describes all the complications of getting such a crowd to pose for an unimaginably complex group portrait painted entirely live, never in a studio. What a book!

Vreeland's magnificent descriptions are perfectly integrated into the action and the amazingly fast-moving plot and interactions among the characters. She provides a wealth of detail about the food, the lives of actresses and women of the demi-monde as well as of the artists and the working class people they know, the rivalries and arguments within the Impressionist group, the exact names and costs of the pigments that Renoir needed for his painting, the poverty suffered by most of the group, and a wide variety of other topics.

Evidently, Vreeland did a substantial research to make it accurate. She wrote:

"My research included such broad topics as the history of the nineteenth century in France, French society and culture, as well as such specific topics as the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris, and the Commune; the changes in the marketing of art from the Salon to independent galleries, along with the famous art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel; the practice of the duel; dressmaking and couture of late-nineteenth-century Paris; Baron Haussmann’s sweeping changes in the look of Paris streets and squares, Montmartre, and quarters where Gustave Caillebotte, Charles Ephrussi, and Madame Charpentier lived; operas current at the time, cabarets and cabaret songs and singers, dance halls and dances, cafés; canotage, the new leisure of boating, styles of rowing craft, the specifics of river jousting, the organization of sailing regattas; transportation and currency; oil paints available at the time, art-supply dealers, color theory, Renoir’s palette and his preferred types of brushes; other painters who figure in the novel, Monet, Cézanne, Caillebotte, Degas, Bazille, Sisley; the tension among the Impressionist painters and the eventual break up of the group; publications popular at the time; the French character, gender roles, and early feminism." (source)

Earlier this week, I posted a set of Renoir paintings that relate to the famous Luncheon of the Boating Party (

here). This review is copyright © 2020 by mae sander. Images are as credited.

Louise-Alphonsine Fournaise – the girl leaning on the railing – was the daughter of the family that owned the water-side restaurant where Renoir's luncheon – and much of the action of Vreeland's book – took place. She worked in the restaurant, helping her mother who was the cook and helping her father with the customers. She was a remarkably self-educated woman, who knew about art and who encouraged Renoir's difficult task of painting a huge multi-person portrait outdoors from life: a very complex endeavor.

Louise-Alphonsine Fournaise – the girl leaning on the railing – was the daughter of the family that owned the water-side restaurant where Renoir's luncheon – and much of the action of Vreeland's book – took place. She worked in the restaurant, helping her mother who was the cook and helping her father with the customers. She was a remarkably self-educated woman, who knew about art and who encouraged Renoir's difficult task of painting a huge multi-person portrait outdoors from life: a very complex endeavor. Aline Charigot – shown with her little dog – was a beautiful but uneducated and nearly illiterate young woman. She appears in Renoir's neighborhood when he stops for a coffee:

Aline Charigot – shown with her little dog – was a beautiful but uneducated and nearly illiterate young woman. She appears in Renoir's neighborhood when he stops for a coffee: