Who was Georges Perec? He was a very talented and accomplished French writer, born in 1936. He published many books between 1965 and his death in 1982. As a member of Oulipo. a French literary society, he was involved with a variety of formal and unusual writing techniques. In particular, he wrote an entire novel without the letter e and then wrote a short story with no vowels other than the letter e.

Perec was very fond of word play and complicated plots and twists in his works of fiction. He was concerned with what he called the “infra-ordinary” side of daily life, and his many books explored it in a number of forms, including prose, poetry, and even the composition of crossword puzzles. He liked jokes too; he wrote erudite spoofs, poems full of tricks and more, and his work is extraordinarily full of allusions to other works of literature.

The biography of Perec reveals a very complicated person. He was orphaned during World War II, when his father died in battle and his mother died in Auschwitz. Once the war ended, he lived with his aunt and uncle, received an entirely French education, worked at a job in a research lab, and published highly acclaimed fiction and other writing. In the course of his life, he associated with many of the most famous thinkers and writers of his era. Perec’s life, in my view, mirrors much about the life of intellectuals in Paris in his time.

Reading a Biography of Georges Perec

Georges Perec: A Life in Words

by David Bellos begins with a history of the author's name: Perec. While it seems to be a Breton name, it's actually a phonetic transcription of Peretz, the original name of Perec's father, who was a Jewish immigrant with a traditional Jewish name. Bellos gives a detailed history of the origins of the Peretz-Perec family's immigration from Eastern European shtetls to Paris France in the decades before Georges' birth in 1936.

Bellos's biography is highly detailed in every way, beginning with the family’s assimilation to life in Paris, the business dealings of several family members, and eventually the way they survived (or didn't survive) during the Nazi occupation and the deportation of Jews to the concentration camps. The survivors spent the war in the Grenoble area; when the war was over they moved back to Paris and more or less resumed their pre-war life. It’s a painful story, especially the death of. Perec’s parents and his time being hidden when he was a small child.

The years just after the allied victory in France brought the family another type of nightmare, one that's not covered in many histories. For the surviving Jews there was an agonizing wait to know what had happened to their deported relatives: a brief period that is rarely covered by history books. After the 1944 Allied victory in France, the government was unable to provide information about these victims. Finally, in June 1945, a huge exhibition at the Grand-Palais was entitled “Hitler’s Crimes." It revealed, for the first time, the fate of the French Jews. It's unimaginable to think of the way this news must have affected the surviving Jewish people of France, including Perec's family.

About the exhibition:

"It presented a chronology of the internment of Jews in the French camps of Pithiviers, Beaune-la-Rolande, and Drancy, in the occupied zone, and at Gurs, near Navarrenx, in southwestern France, under the rule of Vichy. It also gave a tally of deportations from Drancy to Germany: 62,608. ... The exhibition itself was dominated by two wall-size enlargements of photographs of Belsen-Bergen, on loan from the British embassy; there were other images as well of Buchenwald, Nordhausen, Mittelgladbach, and Maidanek. Though there were no pictures yet available of Auschwitz, it must have been obvious what fate had befallen the French Jews deported there from Drancy."

Perec was a small child at this time. From age 5 to 9 he had been required to keep his identity and Jewishness a secret, and forget everything including his lost mother. When his Aunt and Uncle took him into their family, they were required to do excruciatingly painful paper work to prove Perec’s mother Cécile’s “disappearance.” After she had been taken to Auschwitz there was no proof of her fate. They obtained only “a missing person’s certificate for Cécile. It was not a death certificate. It was called an acte de disparition.” Perec thus grew up without clear knowledge of his mother’s end -- but in fact he had too much knowledge.

The future writer had a fairly conventional school career. He recieved a typical French Lycee education until the bacchalaureate, and then spent some time preparing for admission to further education. Having attended prep classes for the Grandes Ecoles examinations, Perec decided (unlike almost all French intellectuals) to drop out, and simply try to be a writer. In fact, he had decided on this ambition at the end of Lycee. For the rest of his life, his principal identification of himself was as a writer.

Once he abandoned the standard educational path, Perec struggled to establish a life in Paris, and he had various part-time jobs while enjoying life with friends and pursuing intellectual interests. During his early 20s he was required to do a term of military service. After training as a paratrooper, his military service included a term as an office worker in Paris, where he returned to life with his friends. His Paris life:

“The moment his duties were done each day, he could step out of the ministry building, dressed in his embarrassing uniform and red beret, walk down Rue Saint-Dominique, go over the Solférino Bridge into the Tuileries gardens and saunter past the statue of Eblé, the least famous of Napoleon’s generals, or alternatively, using the Point-Royal, pass through the Place du Carrousel, then cross Rue de Rivoli, and reach his perch in ten minutes at the most. He would reemerge metamorphosed, wearing (perhaps) a broad-striped red and green pullover, tight trousers, and shoes as unlike military boots as could be managed; and in such or similar informal evening attire, he would head for one or another of his regular haunts to drink with his friends and discuss the major issues of the day, from food to philosophy to film.”

To me, this describes the ideal life of a young person in Paris in the late 1950s! Perec was also trying to write and publish his first novel. His early efforts were not particularly successful, and he drifted around for a while, acquiring an apartment (with money from German reparations) and a wife. He lived briefly in Tunisia, where his wife had a temporary teaching position.

After a long time living on the margins, Perec took a salaried (though low-paying) and stable job as an archivist at a neuroscience laboratory. He was given the job because he had experience creating a file-card system for information retrieval. Though not mathematical, he worked out a way to apply mathematical graph theory to the task of finding articles on neuroscience for the researchers in the lab, and his invention was a remarkable success, while his job left him time to keep on writing. As it happened, a mathematician whom he consulted on graph theory for his job was also a member of the literary group Oulipo, to which he introduced Perec.

In 1965, after ten years of reworking his first novel, Perec published Les Choses — Things. It achieved a slow success, as each small edition sold out with more and more of the young people around Perec’s age, mid-twenties, talked about the way this unusual and very short novel captured the spirit of the 1960s. And: “On 21 November 1965, the Renaudot Prize put Things in the limelight and made Georges Perec a national celebrity if not quite a household name.”

|

Perec wrote many books in the following years.

These are the ones I found in my attic from my past Perec reading projects.

He also worked in film, radio productions, opera, magazines, and other media. |

Perec and Oulipo

Oulipo was a formal group of literary and mathematical creators, who had regular meetings (dinner meetings at restaurants) and discussed a variety of literary forms. One such form was the lipogram, which is a text that is missing one of the letters of the alphabet. Many others, based on mathematical ideas, were also discussed, and some of the members wrote poetry or short works that followed the invented constraints.

Perec took the inventions of Oulipo more seriously than the others -- in 1969 he published a full-length novel called La Disparition, which is a lipogram in e -- that is, it is written entirely without the most common letter in the French language. The plot of the novel centers around disappearance and loss: the characters know something is missing but they can't quite grasp what it is. Remember the "acte de disparition" that proved that the French government did not know what had happened to Perec's mother at Auschwitz? Perec connected the disappearance of the letter to the disappearance of the mother.

Throughout his life, Perec was often treated by psychoanalysts and other analysts, and he was enormously introspective. This seems to have contributed to his genius as an author of unusual and very original writings.

Perec's Writing and Publishing Continues

In the 1970s, Perec continued writing and publishing a variety of things, both directly influenced by Oulipo and not-so-directly. He traveled, including visits to the US and Germany. His personal life was complicated by separation from his wife, and relationships with several other women. In Georges Perec: A Life in Words, Bellos details all of his writing and personal life in great detail, but my summary is already much too long!

An important publication, W or The Memory of Childhood was an autobiographical novel that Perec worked on for years, but completed only in 1974. Alternating with a fictitious story, he tells how his memory of his parents, their disappearance, and his time hiding from the Nazis were unretrievable no matter how hard he tried to remember.

|

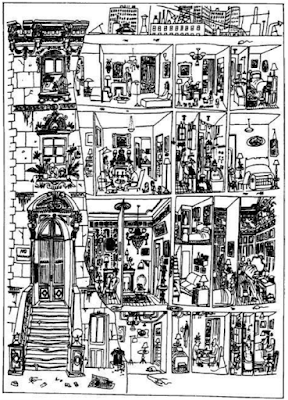

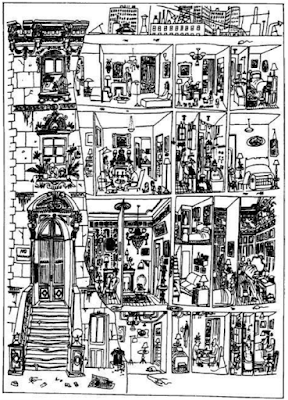

Saul Steinberg: "The Art of Living." 1949.

One of Perec's inspirations for Life: A User's Manual. |

Perec began working on a long and elaborate book called

La Vie: Mode d'Employ or

Life: A User's Manual in around 1972, intensely in 1974. Like the Steinberg cartoon, which he cited as an inspiration, he pictured the rooms of an apartment building, the people living in them, and what they were doing. The various chapters of the book, as he presented it to Oulipo, fit together in a way that Perec imagined was like chess puzzle called a knight's tour. He also described it as "a jigsaw-novel that describes a block of flats in Paris with its façade removed." The book was eventually completed and published in 1978. Essentially, the book defies any simple description of its style. "Perec’s masterpiece is an Oulipian work, but one that is based on the “bending” of all of its constraints."

The book won the Médicis Prize for 1978 -- an important accomplishment in France. He also appeared on the insanely influential French TV program Apostrophes, hosted by Bernard Pivot. And thus became famous and acclaimed as a writer.

Perec's creative life continued with a book he wrote while on a visit to Australia, and with many of the other creative endeavors he had pursued in his life. However, when he returned from Australia, he was diagnosed with cancer, and he died in 1983.

Wrapping up this very long blog post

Georges Perec: A Life in Words is a painfully and painstakingly complete biography, based on numerous interviews with Perec's family, friends, and colleagues as well as on published and unpublished materials. The hardcover edition has 832 pages; this blog post is based on my reading of the book.

The Kindle edition of Georges Perec: A Life in Words is very bad. It is missing the photos and illustrations that are called out in the text; it has no page numbers but it gives cross-references by page number; and it has many transcription errors. My quotes here have no page numbers because they are missing from the Kindle edition.

In conclusion, I'll just ask -- do you think I am totally mad to have patiently read this enormous book? Whatever the answer, I now hope to read and reread some of the actual works by Perec. I'm sharing all of this with the bloggers at Paris in July.

|

The google doodle for March 7, 2016, which would have been Georges Perec's 80th birthday.

I like the subtle erasing of the e -- referring to the book for which Perec is best known. |

Blog post © 2022 mae sander.