“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” — Abraham Lincoln, 1858. (source)

|

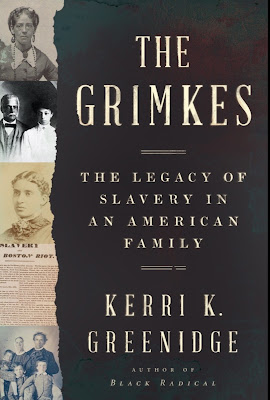

| The Grimkes: Published this month. |

The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family by Kerri K Greenidge is making me think hard about Lincoln’s famous definition, though this quote doesn’t appear in the book. The profound depravity of many slave owners in this historic family, and the indifference and self-centeredness of many of the other White members of the famous abolitionist family is painful to learn about. In the preface, the author states an underlying observation: “The tragedy of the Grimke sisters’ lives was the fact that they never acknowledged their complicity in the slave system they so eloquently spoke against.” The self-awareness and suffering of the slaves, including the Black members of the Grimke family, is equally a torture to read.

"Angelina and Sarah Grimke undoubtedly heard the mob as it made its way down Lombard Street, through Sixth and Seventh and the narrow alleyways in between. And yet they never mentioned, either publicly or to each other, the actions of the city’s enraged white people, nor did they reflect in future writings on the lasting effects of such violence on the Black people they eventually claimed to serve." (pp. 10-11).

Who Were the Central Figures of The Grimkes?

- Sarah Moore Grimke (1792–1873), White daughter of slave owners in South Carolina who became a major participant in the abolitionist movement in Philadelphia and the North.

- Angelina Grimke Weld (1805–1879), her sister, an orator and leader of the abolitionists.

- Archibald “Archie” Henry Grimke (1849–1930), son of their deeply evil and cruel brother and Nancy Weston, a woman who was his slave. With the help of his two aunts, he received a traditional education at several famous institutions, including Harvard, and became a highly educated and influential figure in the late 19th and early 20th century.

- Francis “Frank” James Grimke (1850–1937), his brother, equally educated and prominent.

- Angelina “Nana” Weld Grimke (1880–1958), Archie's daughter, a well-known poet and playwright of the early 20th century.

|

| Sarah Grimke, around 1850 |

"From New Orleans to Charlotte, the slaveholding tradition of white men installing an enslaved Black woman in a slave cabin on his plantation so that she could be sexually available at all times was so common that writers, antislavery and proslavery alike, wrote countless parables about the practice." (p. 113).

Nineteenth-Century Activism

"...most white abolitionists were as blinded by their own self-interests as the Grimke sisters nearly thirty years before had been blinded by their own sought-after redemption. Back then, Sarah and Angelina saw slavery as a sin for white people to vanquish from the land and white deliverance as a just consequence of slavery’s end. Now, in 1862, white men like abolitionist Samuel Gridley Howe and Union Army cotton agent Edward L. Pierce saw impending Black freedom as a force to be controlled and directed by white New Englanders.” (pp. 146-147).

"As Philadelphia’s rapidly industrializing economy led to low wages and underemployment that forced most Black children out of the classroom, poor white children were saved from ignorance and a lifetime of toil by publicly funded charity schools, designed to set the city’s 'destitute' on a path to productive republican citizenship. As one Philadelphia philanthropist informed Alexis de Tocqueville, who was then on his first tour of the nation, colored children were legally entitled to public education, but “the [white] people are imbued with the greatest prejudice against Negroes," (p. 47).

Even the reformers who were more open-minded than most White people did not recognize that Black people wanted the same type of education and opportunity that White people did. After the war, particularly, a system that fostered a supposedly practical education for Blacks appealed to the latent racism in many of the most supportive and committed people.

"At Howard University in Washington, Hampton University in Virginia, and others like them, Native Americans, recently denied citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment; African Americans, recently emancipated in the South; and poor Southern white residents, exploited and degraded by the slaveholding plantocracy, would be trained in 'Christian morality and free labor' as a form of cultural and economic acclimation to a rapidly industrializing America." (p. 213)

This attitude greatly affected the support that the Grimke sisters offered to their nephews, whose education they took responsibility for, but whom they did not treat as real equals:

"It was in this vein that the well-meaning and sincere Grimke sisters ignored the type of education they had always valued for their own children and urged their Black nephews to consider a postsecondary education that emphasized labor as well as humanistic inquiry." (p. 213).

As time went on, the discrepancy grew between the aspirations of willing and able Black people to be educated in a traditional way, and the theory and practice of many educators. This included Booker T. Washington, who offered a different type of education for these "different" people. In reality, the former slaves were treated as unequal and less capable:

"... many members of the colored elite agreed with Washington’s prescription that 'harmony will come [between Black and white ] as soon as we forget the supposed injuries of the past.' The rising generation of negroes, Washington and his supporters believed, were best served by personal and community adherence to 'thrift, moral education, and the cultivation of our own businesses.'” (p. 271).

In The Grimkes, Greenidge offers the often-neglected alternative view held by people like Archie Grimke, that Black and White people both craved and deserved a full set of choices when it came to education and their life work.

There's Much More!

From The New York Times Review

“The Grimke sisters became celebrities, publishing essays that shaped abolitionist thinking and reluctantly stepping into a male-dominated public sphere where they were never completely welcome. Their fame derived from both their words and their deeds. They rejected their white inheritance by coming north and joining the movement, gaining moral credibility that few of their peers could match. But in her new book, ‘The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family,’ the historian Kerri Greenidge challenges this narrative, showing that the sisters’ contributions to abolition and women’s rights were undergirded by the privileges they reaped from slavery. The lives they built, and their relationships with Black relatives, were poisoned by the profits, violence and shame of white supremacy. …

“Sarah and Angelina urged their Black nephews to forget about the past and focus on the future the sisters envisioned for them. Archie became a lawyer and diplomat in Boston, and, later, a national vice president of the N.A.A.C.P.; Frank became a pastor and leader of the Black church in Washington, D.C. Archie and Frank repressed their suffering and worked their way up the social hierarchy. But neither fully healed from the wounds of their enslavement and the denigration of their mother. The respectability they aspired to was saturated with sexist Victorian morality, colorism, and white ideals of intellect and propriety.” — “Slavery’s Indelible Stain on a White Abolitionist Legend,” October 29, 2022.

8 comments:

I can see that this would be an excellent book to look closely at the way many of our most challenging social issues were faced (or not faced) in the past. I've included it on my list of nonfiction books I'd like to read in the future.

Another brilliant book and book review. You are so good at this. Have a great day today.

I cannot express how terrified you must have been to have your grandchildren vulnerable during a mass shooting incident. As for the book, I'm not sure I would use the term relationships when describing the raping of slave women. It's a part of American history we only brushed over in school here.

Wow - what a review! And what a book. It sounds like the kind of book you read slowly to absorb all the information OR that you want to throw against the wall in disgust and frustration. Since I plan to read more NF next year, this will go on the list - thanks for bringing it to my attention.

Terrie @ Bookshelf Journeys

https://www.bookshelfjourneys.com/post/sunday-post-25

This book sounds fascinating -- and a very emotionally difficult read. Thanks for such a comprehensive and thorough review.

Great review! I had never heard of those sisters before!

What a thorough and complex review, which seems fitting for this book. The legacy of slavery is so vast and profound; I don't think most Americans have really dealt with it properly yet.

It sounds scary to know of all the abuse & violence to the slaves & their own children. The Grimke's own brother & father sound horrendous. I first became aware of the Grimke sisters through Sue Monk Kidd's novel The Invention of Wings ... which is a fictionalized account of them which I recall liking. So I was excited to hear of this new book which has received such acclaim. Thanks for your review.

Post a Comment