Do I mind reading about an obsession with tofu, tempeh, seitan,

and soy products in general? Sometimes I do mind.

Sometimes the soy-based mindset of this author does bug me...

No Meat Required: The Cultural History and Culinary Future of Plant-Based Eating

Alicia Kennedy's reasons for eating less meat (or in her case NO meat) started very much like my motivation: she agrees with the principles that gave me and my husband cause to reduce our meat consumption three years ago. Writing about her book, she said:

"To write about food means always occupying the realm of the ordinary. We can be reporting on deforestation for palm oil production, the destruction of mangroves for shrimp harvests, or the atrocious working and animal welfare conditions in industrial meat-processing, but, for the reader, it will all come back to the grocery store, the kitchen, and the menu they’re faced with at a restaurant. How do we navigate this thorny terrain—which includes labor rights, climate change, loss of biodiversity, corporate greed, colonialism—without overwhelming but instead empowering, entertaining, and encouraging that reader?" (source: Navigating the Thorny Terrain of Food Writing)

In reading the book, I wished that she had adhered more to these issues and less towards personality sketches of vegan advocates, owners of vegan restaurants, vegan revolutionaries who want to overthrow the government through diet, feminists who see meat as a tool of the patriarchy, and famous cookbook writers like Molly Katzen or Frances Moore Lappé from the second half of the 20th century.

Sure, I remember those 1970s potlucks where the more hip-type people brought bland casseroles made of lumpy brown rice and greens, probably a recipe from Frances Moore Lappé's Diet for a Small Planet (1971) or Molly Katzen's Moosewood Cookbook (1974). I remember bake sales with carob flavored "brownies" that had so much whole-grain that they took the skin off the roof of your mouth. I remember a health-food store where the bread was moldy and the clerk said that was good because it showed the bread contained no poisonous additives -- yes, I thought, I want to be sick now, not 40 years in the future when the additives might catch up with me. And I remember vegetarian restaurants through the years with a different philosophy every decade.

I did enjoy her descriptions of the way that many food trends and innovations begin small but are taken over by huge money-making corporations and big-money interests. Or of exploitation of desperate and poorly-treated workers who produce specialty foods. The author writes:

“What does it matter if the cashew cheese is vegan if the hands of a woman in India have been irreparably damaged by the nut shell’s toxin? What does it matter if Oatly is in every coffee shop if one of its stakeholders is Blackstone, a private equity firm also invested in a company deforesting the Amazon and led by a CEO who donated $3 million to a super PAC supporting Trump’s re-election? More vegan food doesn’t inevitably lead to a more just world, but it does let a lot of companies greenwash their money-making in its name.” (p. 144)

When I bought Kennedy's book, I signed on for a memory tour of all this "cultural history." Some of it is familiar to me, some is new, some is interesting, and some is boring. But I'm not that enthusiastic about such a long version of vegan history in American life. I just want to eat less meat, and I see it as a humanitarian decision that doesn't need overthinking. By the way — I don't want to eat tofu too often.

In sum: No Meat Required talks much more about people than about food. It's not about vegetables, it's about vegetarians/vegans. It's not about recipes, it's about recipe writers. It's not about cooking, it's about chefs. It's not about eating, it's about theories of eating. It's about the politics of choosing food, whether one shops in a supermarket or a farmers’ market. It’s not about the food itself (except the author’s disgust for eating flesh) but about other concerns like whether one is concerned about big agriculture or about the great profits to be made from artificial meat.

Social issues predominate several chapters of the book. For example, the racism in selecting cookbooks for publication or the bigotry in promoting culinary personalities to media stardom. The author documents a systemic lack of recognition of non-mainstream cultures and cuisines. Mediocre white writers have a much easier time than outstanding minority writers. The various ways that Black groups embraced vegetarianism has been pretty much ignored by the culinary establishment: the author includes interesting discussions of Black writers and popularizers of vegetarian diets.

Food justice, food economics, food history, food as a cause of climate change, and food capitalism -- all are noteworthy topics in Kennedy's book. She describes the history and technology of manufacturing soy milk and cashew cheese, and the products of trendy bakeries and faddish restaurants. She also presents her own experiences and tastes and quirks about food — how she likes nut-based fake cheese but not real dairy cheese; adores tofu, tempeh, and seitan; doesn’t like fake meat and reviles real meat, but likes patties made from grain and beans. She favors mushrooms but completely ignores salad — it doesn’t play a role in her life or in the book. Her dislikes are expressed so much more vividly than her likes, that I wonder if she really enjoys eating at all.

Oddly, Kennedy says very little about basic vegan foods like bread, rice, pasta, fruit, or vegetables. This bothered me: these are the foods I most rely on. Specific example: the word “tomato” only occurs three times in the entire book. Similarly, she mentions potatoes, sweet potatoes, rice, apples, and oranges only a few times each. Her focus is just not on the food!

To summarize: I find the book to be a polemic. Maybe I have written too much about what the author didn’t say — but in the end, it’s not really what I wanted to read.

|

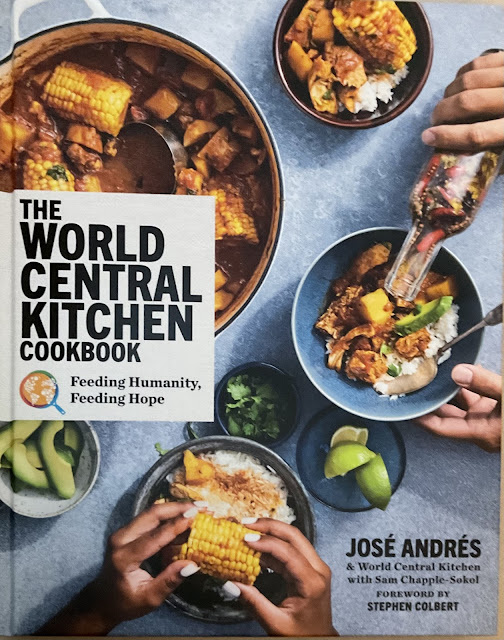

My idea of a vegetarian meal. Even after reading the entire book, I’m not sure mine is the same as her idea.

Note: that’s homemade bread and local corn and tomatoes. ALL her mentions of corn are negative.

|

Review © 2023 mae sander