As I wrote yesterday (here), our local Culinary Historians' summer dinner will have the theme of food during World War II. Therefore, I've been reading about the way that Americans coped with wartime shortages, rationing, and patriotic demands to make do with less. Support for the war effort was broad and deep, beginning on Sunday, December 7, 1941, when the attack on Pearl Harbor definitively brought the nation into the war that was already ongoing in both Asia and Europe. Even individuals who were quite young remembered where they were and how they heard the news, and (for children) how their parents reacted.

Creating Price Controls and Rationing

"There was an enormous opportunity for expanding output as distinct from raising prices. In the war years, consumption of consumer goods doubled. Never in the history of human conflict has there been so much talk of sacrifice and so little sacrifice. ... The war... had almost unanimous support from the people. There was a strong objection to people who tried to circumvent controls. There was a black market, but it was small. There were troublesome moments in the case of meat, but there was a great deal of obloquy attached to illegal behavior." (Terkel, p. 323)

Terkel's interviewees mainly discussed other, broader issues about the war, but a few mentioned rationing and how their communities dealt with it. For example, he interviewed a woman named Sheril Cunning, who was seven years old when the war started, and was living in Long Beach, California. She said:

"My mother and all the neighbors would get together around the dining-room table, and they'd be changing a sugar coupon for a bread or a meat coupon. It was like a giant Monopoly game. It was quite exciting to have all the neighbors over and have this trading and bargaining. It was like the New York Stock Exchange." (Terkel, p. 238)

|

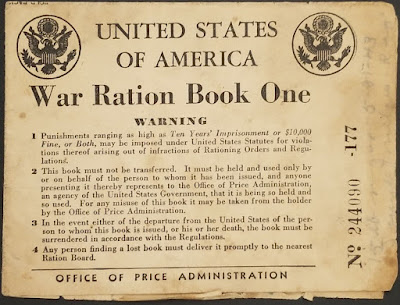

| The text on this War Ration Book warns against trading coupons! |

Another woman, Georgia Gleason of Seneca, Illinois, described working in a restaurant that fed 900 to 1200 factory workers. Her view was;

"What bothered most people about the war was the rationing. They couldn't have everything they wanted. But they all survived it. It was fun, being young, with all that excitement." (Terkel, p. 311)

What did rich people do?

"The food-shop people these days are so bent on showing new substitutes for practically everything on earth that they hardly give you a chance to keep up your acquaintance with old standbys, even though many of these seem to be holding out nicely. Wartime pâtés de foie gras, for example, are all right for what they are, and their makers can be congratulated for showing such resourcefulness, but that's not saying a wartime pâté will do any more for a dry Martini than a bit of anytime smoked trout."

Hibben continues this article with a number of recommendations for merchants in New York that were offering high-quality smoked fish. I don't need to belabor the point about how different this is than the things I've read giving advice to ordinary housewives!

Here's Hibben's advice about entertaining despite rationing: her column from June 12, 1943, subtitled "Doing Nicely" --

"Now that the panic about running short of ration points is over, most people are realizing that, by making a few adjustments it still is quite feasible to entertain in a modest way. Mussels may have to be substituted for roast beef and duckling for a leg of lamb, but for those who prefer a little butter in the company of good friends to more butter all by themselves, rationing and guests can be made to go together quite nicely. The fact is, and we might as well face it, that hostesses who use rationing as an excuse for not inviting us to dinner probably weren't going to invite us to dinner anyway."

A long discussion of how to supply one’s dinner guests with a variety of mixed drinks, such as the julep, then follows. Hibben mentiones that "stocks of bourbon are running mighty low and… getting hold of a drinkable gin has been a chore for some time." Oh, the problems of rich people! I found these little vignettes a fascinating contrast to the challenges to the common people who just wished they could make a Sunday roast and bake a cake the way their mothers had done. Not to mention those who were even more unfortunate — such as the young American soldiers going to war, the Europeans and Asians whose homes had become battle grounds, and the victims of Nazi persecution and death camps.

Blog post © 2023 mae sander

7 comments:

I read this and the previous post with great interest. I was young during WWII (born in 1938) but I do remember some of that time. Mostly the part about my Dad being in the war, wounded in Okinawa and sent home to hospital in a State nearby. One set of Grandparents were farmers and we lived in a very small town surrounded by farms so I suppose food shortages were not severe. I do remember adults talking about ration books little rust-red tokens for something though.

These sound like great readings... and the basis for a fantastic book club discussion. It's been a while since I read anything by MFK Fisher, but I remember being surprised by her work. Despite the fact that she's always classified as a food writer, I'm not so sure that her work is really about food or cooking.

Thanks for including the Studs Terkel anecdote about the families in California trading rationing coupons, like a game of Monopoly. Neither of my parents -- born in the 1930s -- ever mentioned rationing, but both of their families were from hill country, and even when I was in my teens, they still grew or hunted most of their own food, and the kitchen of my father's mother was permeated with the steam from endless days of summer canning.

My grandparents (raised me from birth) never discussed the war. We talked every evening at "supper," but it was about current events and things like my school work. I know nothing about how they survived the war. All I know is, my grandfather was a foreman at an oil company. He was in charge of keeping men and several rigs running smoothly. I suspect the war had little effect on them because he was possibly (?) too old for the war and would have been considered an essential worker, since oil was badly needed for the war effort. However, no matter how much he made, he or my grandmother would NEVER have considered themselves in a class like the New Yorker crowd.

I thoroughly enjoyed this and I love Studs Terkel. I read a great deal of his work while I was in college, but not "The Good War".

A tough read. The rich really had some "problems"...

In my family war was not much discussed.

My dad, who lived in the country, and my mom, who lived in the city, had very different experiences during the war. My dad's diet was primarily the vegetables that were grown on his farm, so little changed with rationing. My mom's family had lots of trouble finding meat and sugar and butter, staples of their diet.

Not sure it's related, but my dad has now lived twenty years longer than my mom.

I'm still looking at the cover of the New Yorker with a price of 15cents! My parents never talked about the food rationing. My sister was born in 1938 and experienced many shortages. That may be why when she married in the 1960s, she always had too much food in the pantry. Very interesting posts.

This is fascinating, Mae. I confess, it's something I hadn't thought of! My grandparents got by largely on their farm veg and buying meat and staples as allowed. That's a great cover.

Post a Comment