Rice in Japanese History and Cuisine

I've been rereading the book

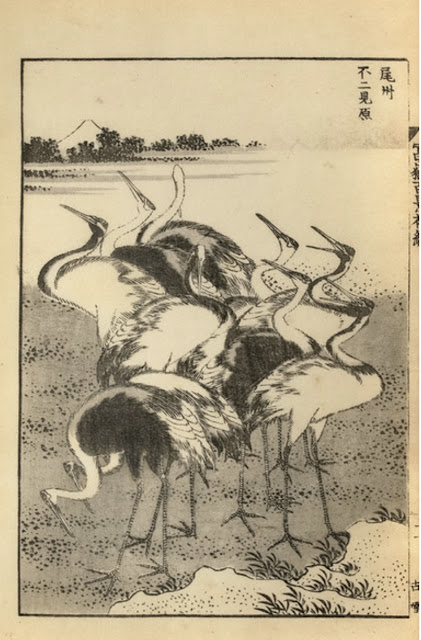

Rice as Self by Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, which mentioned the many images of rice cultivation by the famous artist Hokusai (1760-1849), whose works I included above. Not long ago, I reviewed this book in

a blog post here.

Ohnuki-Tierney, a scholar of Japanese history and sociology, presents the role of rice in Japan from the earliest times, including the ways that rice was part of culture and mythology and the ways it was essential to the divinity of the Emperor and to the development of nationalism before World War II. The author also documents the way that the Japanese diet has shifted away from rice in recent times, up until the early 1990s (when the book was published). I’ve checked a few more recent sources, and rice consumption in Japan has continued its decline in the ensuing 30 years.

I especially enjoyed the description of gods and god-like characters that had a role in defining the importance of rice in Japanese life. For example, Amaterasu, the sun goddess, had a great-grandson called Amatsu Hiko Hiko Hohotemino Mikoto — that is “a male child of the Sun Goddess and Lord of rice stalks with numerous heads.” As a god of rice culture, he predominated over his brother, a sea-god. Significantly, this rice-god became the ancestor of the first Emperor, whose descendants have been the Japanese Emperors ever since that time. (p. 52)

The Emperors of Japan were eclipsed by the actual political and military rulers, the Shoguns, for several centuries. During the Shoguns' rule, Japan was cut off from international contact. In 1868, the Emperor Meiji was restored to actual power, the beginning of vast changes, also initiated by the opening of the country to foreigners -- forced by the military presence of Admiral Matthew Perry whose ships had arrived in 1853.

The whole new era demanded a whole new national myth, which included a definition of rice as the key to nationalistic food ways. Rice had always been an important and sacred food, but now it became an even more important aspect of the Emperor as a divine being who symbolized the nation. The process of creating this national myth is fascinating and very complicated, especially as the era was simultaneously a time of rapid westernization of Japan, including the adoption of technology, literature, clothing styles, and many other features of European and American culture -- including food.

The central place of rice developed right alongside of the introduction of much more meat to the Japanese diet. So complicated! A symbolically national meal developed partly from an existing tradition of elaborate banquets where small elegant dishes, mainly vegetables, were served with rice as the final course. This Kaiseki meal is still served by very upscale restaurants in Japan, as a kind of ideal, not an everyday menu.

The militarization of Japan in the prelude to World War II, and the terrible destruction and reconstruction of the post-war era, was a time of much more modernization of Japan, but with a definition of the exceptional Japanese essence. During the postwar era, American wheat was shipped in to prevent mass hunger, and was mainly used for another traditional inexpensive and popular dish: ramen noodles. Nevertheless, rice remained as the national staple and ritual food, even as rice consumption dropped -- on average, people had eaten 5 bowls of rice per day, and now they eat one, or even have some days without rice. Bread consumption recently surpassed rice consumption, and the Japanese now eat a highly varied diet. But there is still a high value place on eating rice that has been grown in the rice paddies of the nation, just as it was valued in the early 19th century when Hokusai's iconic images were created.

Exploring a National Dish

The question of what is the real national food of Japan is the subject of one chapter in Anya Von Bremzen’s recent book

National Dish (I wrote about the chapter on France last month in

this post.)

She, as well as Ohnuki-Tierney, describe how first Chinese food and later Western food entered Japanese foodways — both quote the saying

“Wakon yosai” which means “Japanese spirit, Western learning.” Von Bremsen writes of this motto:

“I recalled the famous Meiji period motto describing essentially the native genius for adapting and appropriating—Japanizing and indigenizing—borrowed ideas. Of course before Meiji, the saying was wakon kansai, or ‘Japanese spirit, Chinese learning.’” (National Dish, p. 102)

Which is more popular in Japan: noodle bowls or rice? Or have they been overtaken by pizza, hamburgers, or other Western dishes? What’s most popular in the Japanese convenience stores (like Seven-Eleven)? Many Japanese people rely on these stores for buying much of their food.

Von Bremzen writes:

"Noodles as such arrived in Japan with Chinese Buddhist monks around the twelfth century. But it took another eight centuries for a dish recognizable as ramen (noodles + meaty savory broth + toppings) to emerge as a popular snack dispensed by yatai pushcarts and cheap Chinese restaurants." (p. 88)

She summarizes the question of which is more essential: ramen noodles or rice:

"Ramen and rice, rice and ramen. They made a curious dialectical binary: one a Chinese-origin hybrid that eventually relied on imported American wheat, the other a homegrown treasure imbued with a near-mystical aura as the 'edible symbol' of the Japanese self. Fast versus slow, appropriation versus tradition. And yet both were part of the national food canon: rice, a hallowed cornerstone of washoku (a timeless and supposedly ancient ideal of an ur-Japanese meal); ramen, the 'naturalized' modern star of kokuminshoku, inexpensive 'people’s cuisine,' one that fueled Japan’s post-WWII reconstruction and boom." (pp. 78-79).

Her attempts to figure out what food is most important there took place during a rather amusing stay in Tokyo a few years ago. Like Ohnuki-Tierney, Von Bremzen concludes that despite the decline in rice consumption, Japanese people still have an actual reverence for rice: it’s the soul food of Japan no matter how much or how little they eat, and no matter how much more flavorful and deliciously aromatic other choices may be.

A Formal Japanese Meal

|

A small plate of food from a Kaiseki meal: one of many elaborate dishes.

Evelyn is in Japan, and had this meal a few days ago. |

|

| The rice served at the formal meal, with tea. |

Blog post © 2023 mae sander