Van Gogh's Table: At the Auberge Ravoux provides a fascinating study of Vincent Van Gogh's developing relationship to food and how it was reflected in his art. The biographical chapter of

Van Gogh's Table is by Fred Leeman, a former director of the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam. A chapter by Julia R. Galosy documents the post-Van Gogh history of the Auberge Ravoux, in Auvers, France, where Van Gogh boarded and painted at the end of his life. In addition, a chapter of food history and recipes by Alexandra Leaf demonstrates three types of French food that Van Gogh may have eaten: popular cuisine, bourgeois cuisine, and country cuisine from locally sourced ingredients.

Leeman's biography begins with a description of Van Gogh's early life, when he aspired to paint and also to be a Christian preacher like his father. As a young man, Van Gogh lived with poor people in his native Holland, and ministered to them as well as sketching or painting their lives. "The Potato Eaters" thus reflects not only his emerging artistic vision, but also his belief that

bread -- that is, very simple peasant food -- was an appropriate diet for a person of his spiritual and religious temperament. His letters from this time express his views, documenting that he often lived on crusts of dry bread, coffee (which the peasants in the painting are also drinking) and little else, often going for long times between enjoying warm meals.

|

| Van Gogh: "The Potato Eaters" |

Later, Van Gogh lived in the south of France and ultimately in Auvers, a village just outside Paris, where he died. His emergence as a mature and innovative artist during this time is well-known, as he invented his characteristic use of color, light, and human hands and faces. For example, the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, which I visited last summer, is currently organized around his biographical and artistic development.

|

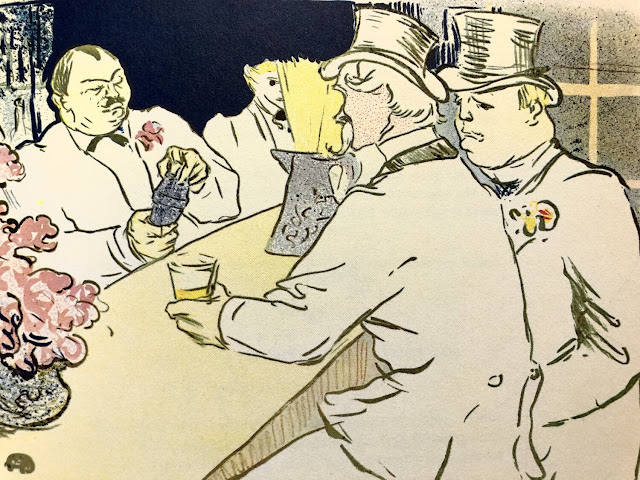

Toulouse-Lautrec: "Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh

in the Cafe du Tambourin", Paris, 1887.

Van Gogh appears to have a glass of absinthe. |

|

Van Gogh: "A Table in Front of a Window

with a Glass of Absinthe," Paris, 1887 |

As Van Gogh encountered French artists and French culture, he also became familiar with a variety of foods in cafes and various types of restaurants frequented by his fellow artists -- meals there frequently consisted of meat dishes, bread, vegetables, cheese, and simple desserts.

Van Gogh's Table has reproductions of a large number of paintings in which he depicted cafes, restaurants, diners, and other food imagery. In Auvers, Van Gogh lived in the Auberge Ravoux where he paid 3.5 francs per day for room and board. He feared that his earlier abstention from all but a minimum of food had harmed his health -- which also had suffered from his increasing consumption of wine, absinthe, and copious quantities of coffee.

Dr. Gachet, whose face is familiar from Van Gogh's portrait of him (above), played a large role in the last months of the painter's life when Van Gogh lived in the Auberge Ravoux. The chapter titled "Sunday Lunches with Dr. Gachet" by Leaf is especially informative. Van Gogh was a patient of Dr. Gachet, but also engaged in a warm relationship with the doctor's family, and dined at their home once or twice a week. "Feeding the painter was part of the doctor's therapy," as he presided over conversations about "art, politics, free love, and homeopathy."

One Sunday dinner in June of 1890 at Dr. Gachet's home included the doctor and his wife and son Paul, Vincent, his brother Theo Van Gogh, Theo's wife Johanna, and a Madame Chevalier. Theo and Johanna's baby was with them, though not at the table, evidently. "An atmosphere of joy generated by fine food, excellent wine, and freely flowing conversation reigned that day, as later recounted by Johanna, Paul Gachet, and Van Gogh."

|

| Van Gogh: "Margurite Gachet in the Garden," 1890. |

On another occasion a few days later, the Gachets invited Vincent to celebrate their son's 17th and daughter's 21st birthdays in their garden. Leaf's recipes for cuisine bourgeoise suggest what might have been on the menu at Dr Gachet's house: she gives recipes for asparagus with Hollandaise sauce, Fillet of Striped Bass with Panfried Leeks and Buerre Blanc, Roast Duck with Chanterelle Fricassee, and Cherry Clafouti.

The book also includes an extended history of the Auberge Ravoux itself, which was never much changed after Van Gogh's famous death there. In the 1950s and later, it was used as a set by several famous film-makers, and has become a tourist attraction for Van Gogh fans.

|

Van Gogh, "Bowl with Potatoes," Arles, 1888.

Contrast this to the images of the "Potato Eaters." |

The link between Van Gogh's creative development and his changing views on eating makes this one of the most fascinating books about food and art that I've read.

That Van Gogh in France not only discovered color and light but also at least to some extent became aware of the taste of food, and thus reduced denying himself the enjoyment of eating is amazing! No less amazing is how productive Van Gogh was in Auvers: in 70 days there, he painted approximately 70 masterpieces, as I learned at the Van Gogh museum.

It would be fascinating to try to recreate one of the dinners documented in the recipe chapters!