Trevor Noah's memoir,

Born a Crime, is an enormously powerful exploration of a number of issues. These issues arise from the politics of apartheid life for Black and colored people in South Africa, from Noah's mother's determination to give him opportunities to flourish in spite of all the restrictions, and from his awareness of the culture of the deprived populations of the country, particularly his mastery of their many languages and of the meaning of the entire Black population being deprived of education.

The title of the book refers to Noah's birth: because his mother was a Black South African and his white father was Swiss, his birth in 1984 was a very serious crime. As a small child, he was hidden by his family -- not allowed to play outside of his own small yard for fear he would be taken away from his mother by the authorities. He writes:

"If you ask my mother whether she ever considered the ramifications of having a mixed child under apartheid, she will say no. She wanted to do something, figured out a way to do it, and then she did it. She had a level of fearlessness that you have to possess to take on something like she did. If you stop to consider the ramifications, you’ll never do anything. Still, it was a crazy, reckless thing to do. (p. 22).

I've read many memoirs of people of exceptional accomplishment who came from the worst imaginable backgrounds and environments. They almost all have one thing in common: a remarkable mother. Noah's mother was such a figure, as the above quote suggests. She was determined to seize freedom despite the repressive and outrageous policies of her country. She valued education and independence. She was highly religious and enforced church-going on her family.

Unfortunately, at a certain point, somehow, Noah's mother enmeshed herself in a hideous marriage where she was abused physically and mentally. His portrayal of this dysfunctional relationship is one of the great accomplishments of the memoir, and he offers huge insights into the plight of an abused woman:

"Growing up in a home of abuse, you struggle with the notion that you can love a person you hate, or hate a person you love. It’s a strange feeling. You want to live in a world where someone is good or bad, where you either hate them or love them, but that’s not how people are." (p. 267).

To summarize his mother's incredible contribution to his formation, Noah writes:

"My mother had exposed me to a different world than the one she grew up in. She bought me the books she never got to read. She took me to the schools that she never got to go to. I immersed myself in those worlds and I came back looking at the world a different way. I saw that not all families are violent. I saw the futility of violence, the cycle that just repeats itself, the damage that’s inflicted on people that they in turn inflict on others. I saw, more than anything, that relationships are not sustained by violence but by love." (p. 262).

Noah offers fascinating descriptions of the interactions among the members of various tribes who lived in the Black town where he grew up, as well as of the grinding poverty in which they lived and their constant fear of the police who terrorized the neighborhood -- he calls it the "hood" because of the compelling interest in and imitation of American culture there.

Noah offers lots of little details that make it fun to read despite the grimness. Some of these details involve the food ways of his friends and family. He illustrates the influence of America, like the popularity of KFC and McDonalds, as well as that of popular music. Sometimes he describes what it's like to be nearly starving because there's no money to buy food -- for example, people ate worms and clay. Here's a description of a cheap meal:

"There’s a meal you can get in the hood called a kota. It’s a quarter loaf of bread. You scrape out the bread, then you fill it with fried potatoes, a slice of baloney, and some pickled mango relish called achar. That costs a couple of rand. The more money you have, the more upgrades you can buy. If you have a bit more money you can throw in a hot dog. If you have a bit more than that, you can throw in a proper sausage, like a bratwurst, or maybe a fried egg. The biggest one, with all the upgrades, is enough to feed three people. For us, the ultimate upgrade was to throw on a slice of cheese. Cheese was always the thing because it was so expensive." (p. 207).

More shocking food descriptions are also present, perhaps intentionally to jar the American reader:

"After lunch, business would die down, and that’s when we’d get our lunch, usually the cheapest thing we could afford, like a smiley with some maize meal. A smiley is a goat’s head. They’re boiled and covered with chili pepper. We call them smileys because when you’re done eating all the meat off it, the goat looks like it’s smiling at you from the plate. The cheeks and the tongue are quite delicious, but the eyes are disgusting. They pop in your mouth. You put the eyeball into your mouth and you bite it, and it’s just a ball of pus that pops. It has no crunch. It has no chew. It has no flavor that is appetizing in any way." (p. 214).

Completely conventional food is also here, like the meal his father would cook when Noah visited him on Sunday afternoon -- of course they could not live in the same place, which would have been an immediately obvious crime. Sunday lunch:

"He’d ask me what I wanted, and I’d always request the exact same meal, a German dish called Rösti, which is basically a pancake made out of potatoes and some sort of meat with a gravy. I’d have that and a bottle of Sprite, and for dessert a plastic container of custard with caramel on top." (p. 106).

I think you can see what a vivid and readable book this is, but there's always the horror of the apartheid situation.

What is Apartheid?

Noah's exploration of the meaning of apartheid is another great accomplishment of this book. He writes:

"Apartheid was a police state, a system of surveillance and laws designed to keep black people under total control. A full compendium of those laws would run more than three thousand pages and weigh approximately ten pounds, but the general thrust of it should be easy enough for any American to understand. In America you had the forced removal of the native onto reservations coupled with slavery followed by segregation. Imagine all three of those things happening to the same group of people at the same time. That was apartheid." (p. 19).

The strategy of apartheid, Noah points out throughout the book, was to create wedges and hatred among the many groups. Here is one of his many ways to elucidate the consequences of that cultivated antipathy:

"The worst way to insult a colored person was to infer that they were in some way black. One of the most sinister things about apartheid was that it taught colored people that it was black people who were holding them back. Apartheid said that the only reason colored people couldn’t have first-class status was because black people might use coloredness to sneak past the gates to enjoy the benefits of whiteness. That’s what apartheid did: It convinced every group that it was because of the other race that they didn’t get into the club. (pp. 119-120).

Apartheid also profited from the utter lack of education offered to Black children. Among many consequences was that after apartheid ended, this perpetuated -- unlike German schools teaching the Holocaust or British schools teaching about the many aspects of colonialism:

"In South Africa, the atrocities of apartheid have never been taught that way. We weren’t taught judgment or shame. We were taught history the way it’s taught in America. In America, the history of racism is taught like this: 'There was slavery and then there was Jim Crow and then there was Martin Luther King Jr. and now it’s done.' It was the same for us. 'Apartheid was bad. Nelson Mandela was freed. Let’s move on.' Facts, but not many, and never the emotional or moral dimension. It was as if the teachers, many of whom were white, had been given a mandate. 'Whatever you do, don’t make the kids angry.'" (p. 183).

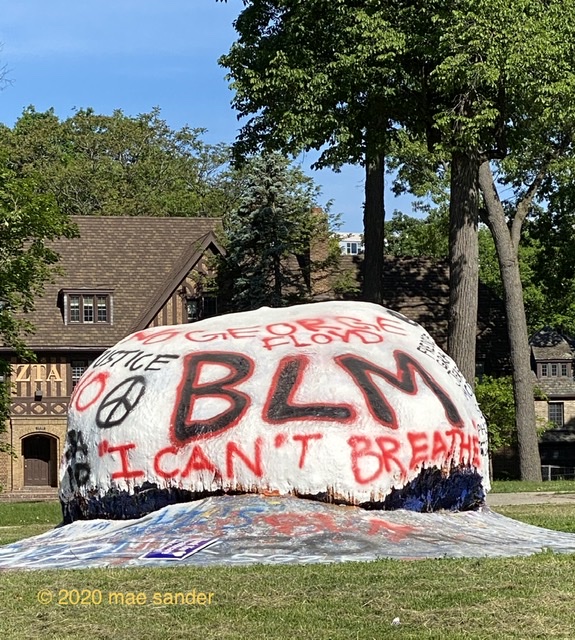

I don't feel it's appropriate for me to compare the apartheid policies in South Africa to the current situation in the United States, but of course I was thinking about it throughout my reading of

Born a Crime, a book that's been on my list for months. Yes, the life conditions of Black and colored Africans under apartheid were horrendous, and still are horrendous despite the end of the formal and legal restrictions. South Africa was and probably is indisputably worse than anything here, but that doesn't change the need for our vigilance and openness to improvement in our own society.

This review © 2020 mae sander for maefood dot blogspot dot com.