“I do not speak the Turkish language, unfortunately, but I guess I speak the Turkish cuisine.” So says Armanoush, a young woman from an Armenian-American background, to her Turkish hostesses in Istanbul. (p. 156)

“I do not speak the Turkish language, unfortunately, but I guess I speak the Turkish cuisine.” So says Armanoush, a young woman from an Armenian-American background, to her Turkish hostesses in Istanbul. (p. 156)

I just read an important and unexpected article: "Meltdown in your wineglass? A conference in Barcelona looks at the effects of global climate change on the world of wine" by Corie Brown in the Los Angeles Times.

I just read an important and unexpected article: "Meltdown in your wineglass? A conference in Barcelona looks at the effects of global climate change on the world of wine" by Corie Brown in the Los Angeles Times.

"Chalk it up to a lucky confluence of events. Most small dairy farmers cannot keep afloat selling milk to large processors at commodity prices, so those who are trying to survive are looking for alternatives. At the same time there is an increasingly sophisticated public that appreciates the difference between mass-produced dumbed-down food and the handiwork of a small dairy that has learned to produce exceptional butter or yogurt or ice cream by doing it the way it was done before World War II, when there was a creamery in every town."

Besides the high price, I suspect that an unnamed problem is that these farmers are limited by industry-sponsored regulations about what they can put on their labels. For example, they may be raising their cows without artificial hormones, but in some states, they can't use this as a selling point.

Locally in Ann Arbor, Zingerman's Creamery is an example of this movement, though not mentioned in the Times article.

"Bowing to the interests of corporate cheese and ice cream manufacturers, the folks at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) appear poised to change the definition of the popular white liquid. Last week they extended the public comment period on a regulation that will allow processors to use a substance called 'ultrafiltered milk' and list it as simply 'milk' on ingredient lists.

"The proposed changes have sparked outrage from farmers’ organizations, who point out, rightly, that there is a vast difference between real milk and the ultrafiltered stuff—also called milk protein concentrates. As the name implies, ultrafiltered milk has been passed through a fine membrane that retains large molecules such as protein and fat, while allowing smaller molecules like water, lactose, and little things called vitamins and minerals to wash away.

"The concentrated fat and protein is cheaper to transport than milk, which explains why manufacturers like it so much. Under current rules, they are free to use the product ... but they must list it as 'ultrafiltered milk' or 'milk protein concentrates' on the ingredient label.

"But ... the industry ... claims that it is 'impractical to comply with the labeling requirements' due to 'economic and logistical burdens.' To add one extra word to their labels? Give me a break.

"You’d think they’d have come up with something better than that. But then, with the FDA firmly in the corporate camp, they don’t need to. Profits will probably trump the rights of consumers to know what’s in their cheese." --

See: Barry Estabrook "Politics of the Plate: Milking It for All It’s Worth."

I feel strongly that the current administration has given free rein to the worst of our society. What else will they do while they are such lame, lame ducks? The farmers' industry website linked above says: "A 2001 investigation by the federal government’s General Accounting Office (GAO) reported ultra-filtered milk is not nutritionally equivalent to fluid milk." As usual, the bureaucrats aren't even accepting the results of their own scientists when it's more convenient for their clients to deny them. I linked to the government website and registered my objection.

The American Indian museum is on the National Mall across from the Capitol, among all the many branches of the Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Art. Its collection of American Indian artifacts is outstanding, but its restaurant, the Mitsitam Native Foods Café, upstages the museum, as far as I'm concerned. It follows the pattern of self-serve restaurants in the many museums on the Mall: a number of specialized stations. Instead of salads, grilled foods, full meals, and sandwiches this cafeteria has stations representing the Plains Indians, the Southwest Indians, South and Central America, the Pacific Northwest, and the Eastern Forests.

The American Indian museum is on the National Mall across from the Capitol, among all the many branches of the Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Art. Its collection of American Indian artifacts is outstanding, but its restaurant, the Mitsitam Native Foods Café, upstages the museum, as far as I'm concerned. It follows the pattern of self-serve restaurants in the many museums on the Mall: a number of specialized stations. Instead of salads, grilled foods, full meals, and sandwiches this cafeteria has stations representing the Plains Indians, the Southwest Indians, South and Central America, the Pacific Northwest, and the Eastern Forests.

It takes 162g of oil and seven litres of water (including power plant cooling water) just to manufacture a one-litre bottle, creating over 100g of greenhouse gas emissions (10 balloons full of CO2) per empty bottle. Extrapolate this for the developed world (2.4m tonnes of plastic are used to bottle water each year) and it represents serious oil use for what is essentially a single-use object. To make the 29bn plastic bottles used annually in the US, the world's biggest consumer of bottled water, requires more than 17m barrels of oil a year, enough to fuel more than a million cars for a year. (See It's just water, right? in the Guardian Online.)

An Israeli friend told us that at the Diana Restaurant in Nazereth we could find hommus that was "poetic." In our view, though, it had strong competition from the other 18 mezze plates served before the meal. All of the food was delicious. The man who prepared the minced meat was a real showman.

An Israeli friend told us that at the Diana Restaurant in Nazereth we could find hommus that was "poetic." In our view, though, it had strong competition from the other 18 mezze plates served before the meal. All of the food was delicious. The man who prepared the minced meat was a real showman. We took the above photo in a restaurant in a Druze village near Mount Carmel, where we spent one Saturday afternoon with Eschel and Michol. These pictures date from our 5 month stay in Israel in 1997 -- before we had a digital camera. We just replaced our old scanner with a new one, and so I decided to try it out and scan some of these old photos.

We took the above photo in a restaurant in a Druze village near Mount Carmel, where we spent one Saturday afternoon with Eschel and Michol. These pictures date from our 5 month stay in Israel in 1997 -- before we had a digital camera. We just replaced our old scanner with a new one, and so I decided to try it out and scan some of these old photos.

"It must be Mediterranean food," I always said in my kitchen in Alicante, "because I can see it from here." Above, you can see a meal I prepared, with food from a wonderful covered market up the coast from our high-rise apartment.

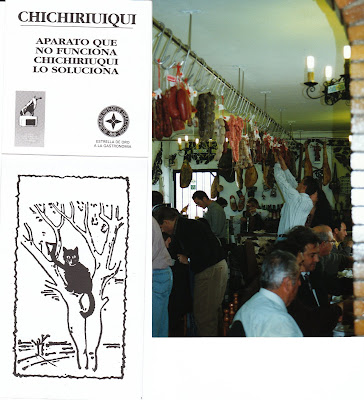

"It must be Mediterranean food," I always said in my kitchen in Alicante, "because I can see it from here." Above, you can see a meal I prepared, with food from a wonderful covered market up the coast from our high-rise apartment. Our friends later took us to a very amusing restaurant, which was sort of pretend medieval. The food was served on trenchers. Smoked meat was cut down from the rafters when you ordered it. The host teased everyone constantly, and even the business cards were a joke.

Our friends later took us to a very amusing restaurant, which was sort of pretend medieval. The food was served on trenchers. Smoked meat was cut down from the rafters when you ordered it. The host teased everyone constantly, and even the business cards were a joke.

Five thousand years ago record keepers in the early civilization of Mesopotamia invented cuneiform writing on clay tablets. In the hands of modern scholars, half a million of these tablets have revealed the lives, customs, literature, arts, technology, folklore, military history, political life, mythology, and religion for thousands of years of this civilization.

Five thousand years ago record keepers in the early civilization of Mesopotamia invented cuneiform writing on clay tablets. In the hands of modern scholars, half a million of these tablets have revealed the lives, customs, literature, arts, technology, folklore, military history, political life, mythology, and religion for thousands of years of this civilization.