I am reading a translation of the cookbook by Bartolomeo Scappi, head cook for several popes and prelates in the sixteenth century.* Descriptions and engraved illustrations present much information about cooking equipment, about the kitchens and associated prep- and store-rooms where he worked, and about the raw materials available for the large-scale endeavor. Scappi thus provides a comprehensive vision of just how he and his numerous staff prepared the meals for his employers.

I am reading a translation of the cookbook by Bartolomeo Scappi, head cook for several popes and prelates in the sixteenth century.* Descriptions and engraved illustrations present much information about cooking equipment, about the kitchens and associated prep- and store-rooms where he worked, and about the raw materials available for the large-scale endeavor. Scappi thus provides a comprehensive vision of just how he and his numerous staff prepared the meals for his employers.The level of effort required and the constant need to carefully select, clean, and process foods is quite a surprise to me. Some details are just amazing: one recipe calls for eggs that have been laid on the same day, another for day-old eggs. Food history authors do not usually dwell on this aspect of Renaissance food preparation.

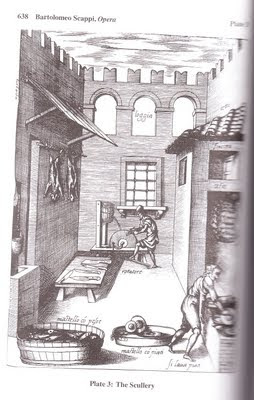

Each meat recipe describes in detail how to clean and prepare the meat prior to cooking: most recipes include multiple steps such as aging, simmering, soaking, and spit-roasting. Some parts of animals had to be cooked immediately or they would spoil. Others had to hang for a while to tenderize the meat. In the illustration of the scullery (above right) animals are hanging up so that the meat will age. It's evident that what came into the kitchen was whole, unprocessed carcasses, freshly slaughtered.

Scappi's recipes constantly warn against using rancid, dirty, or spoiled ingredients. Even salt and sugar must be inspected for contamination, and much of the work involved appears tedious and unpleasant beyond anything in a modern kitchen. Excerpts:

- "...stick [a calf's loin] with lardoons of pork fat that is not rancid" (153),

- "With the hair removed and the [suckling calf's] head clean, take out the tongue...tie up the snout... If you want it skinless, though, when all the dirt has been cleaned off it you can optionally replace the tongue with prosciutto but not blanch the head." (147)

- "Cook two pounds of very clean rice..." (225),

- "Split [a goat's head] in half, washing it in several changes of water, especially those little passages that are often full of mucous. To stuff it, dig out the brains..." (174),

- "...a bit of prosciutto or else a large sausage that is not rancid" (148),

- "Get a thrush in its season... That bird must especially be fresh to be good. Pluck it dry, without drawing it, and sear it on the coals... Spit it crosswise between bay leaves and slices of pork fat or sausages." (203)

- "Get a casserole pot with a pound of clean water..." (273)

Detailed description of each type of fish available include what seasons it was caught, regional names and variants of the species, and where the best ones came from. Sometimes preparation sounds beyond challenging. For example: "Get young lamprey and kill them in a sweet white wine. Take them out of the wine, remove the slime on them in warm water and wash them. Then drain their blood, catching it and setting it aside mixed with orange juice so it will not coagulate." The lamprey then have to be soaked in oil, pepper, salt, and vinegar or verjuice for a quarter of an hour. Afterwards they can be grilled and basted, and served with a sauce or rolled up and sauteed. A really large number of people must have labored in that multi-room kitchen.

Many of the preparations and recipes are somewhat familiar. A few resemble dishes that are still popular in Italy; others are frequently described by food historians. I plan to post more about the dishes that are described in this very interesting work.

*The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570): L'arte et prudenza d'un maestro Cuoco, translated and with commentary by Terence Scully, 2008.

I'm in awe of the fact that you have the patience and ability to embrace such a translation, Mae.

ReplyDeleteI must admit, I'm not sure I would attempt such an endeavor. I do wish I did though. There's so much to learn and be thankful for. It's just a reminder, if these tasks were not explored by those who came before us, what road would travel now?

I'm going to have to tell Janet, The Old Foodie about this most entrancing post.

Thanks for sharing...

I hope it's clear that the book I'm reading _is_ a translation into English of the original Italian cookbook, although the title of the English edition contains the original Italian title. I'll be posting more as I continue reading the interesting recipes.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete