Is France a “McDonald’s-couscous-steak-frites society”? Anya von Bremzen asks. In her very recently published book National Dish (p. 21) she suggests that this global summary characterizes the real food of Paris right now. She considers a number of other possibilities for the French national dish, and concludes that the top candidate is the very classic family dish pot-au-feu, which consists of several types of meat, marrow bones, and vegetables slowly simmered in broth.

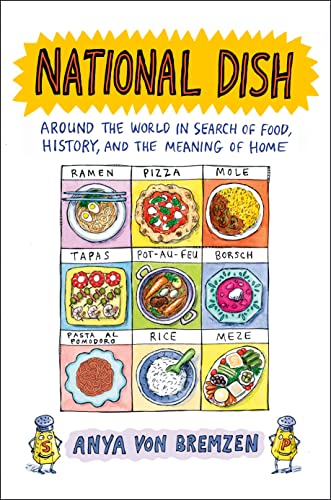

In this post, I have focused on the one short chapter about France and pot-au-feu. This long book also describes the national dishes enjoyed in Naples, Tokyo, Seville, Oaxaca, Istanbul, and the author’s native Russia. If you want to learn more about iconic dishes like pizza, pasta, ramen, rice, tapas, mole, and Turkish cuisine, I recommend that you read this fascinating book!

The first chapter of the book, "Paris, Pot on the Fire," explains Von Bremzen's commitment to the idea of a national dish in France and several other places. She points out the challenges and contradictions to the continued existence of such iconic dishes in multi-ethnic societies such as modern France. In particular, she describes her temporary life in Paris, renting an apartment in the 13th arrondissement. She explains how she attained her goal of making a complete and traditional French meal. This ideal French meal, she points out, has even been recognized by UNESCO in their list of items of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The author first presents her vibrant neighborhood in Paris, where residents come from many places other than France. She describes how she purchased materials for the pot-au-feu at her local shops, and how the locals who were also shopping along with her reacted to her plan to make the classic dish. Finally, on a hot day in a small, small kitchen in her temporary apartment, she cooked and served the entire multi-course meal to her mother and her partner Barry.

Here is the menu, with notes about the sources of the ingredients and recipes, such as M. Larbi the butcher and the famous 19th century chef and cookbook author Careme.

“It was a beautiful museum piece of a meal. We started with apéros of Lillet with œufs mayonnaise and Rousseau-worthy ruby-red radishes with sunshine-yellow butter. Our appetizer proper was that French millennial Instagram darling, pâté en croûte—an architectural Caremian pastry case from the sleek food hall of Galeries Lafayette, housing a mosaic of pork farce, truffles, and foie gras. “Mmmm,” approved my mom as we slathered globs of artery-clogging bone marrow on an award-winning baguette from our local Tunisian baker. Carême’s amber pot-au-feu broth followed, in dainty porcelain cups, succeeded by M. Larbi’s excellent halal boeuf, chicken, and veal, all overcooked by me but not tragically—and concluding with oozy Camembert (France’s 'national myth,' as one anthropologist called it) and glossy darkly chocolaty éclairs decorated with gold leaf.” (pp. 25-26).

|

| Pot-Au-Feu was such a classic that at least one culinary magazine used that as its name. Here's the cover from July 15, 1896 with an idealized cook tasting the famous broth from her pot. |

"This affliction, pari shōkōgun, was the extreme shock suffered by dreamy Japanese visitors at the reality of Paris versus the myth. What traumatized them was that instead of Chanel-clad couples toting Louis Vuitton bags along cobblestone streets en route to romantic bistros, they encountered a scruffy globalized metropolis full of junk food and street trash and ugly scenes in the metro." (pp. 27-28).

I'll wrap up with Von Bremzen's summary of what "national" cuisines and "national" identities mean:

"National cuisines, one food studies scholar observes, suffer from 'problematic obviousness.' The same could be said for the very idea of 'national.' Most of us take a view of nations as organic communities that have shared blood ties, race, language, culture, and diet since time immemorial. Among social scientists, however, this 'primordialism' doesn’t hold water. Scholars ... have persuasively argued that nations and nationalism are historically recent phenomena, dating roughly to the late Enlightenment—and to the French Revolution in particular, which supplied the model for our contemporary concept of the nation, as France’s absolutist monarchy of divergent peoples and customs and dialects was transformed into a sovereign entity of common laws, a unified language, and a written constitution, ruled in the name of equal citizens under that grand idealist banner: Liberté, égalité, fraternité!" (p. 3).

|

| This image shows how a classic pot-au-feu might be served. The broth would be a separate course. Source: Marie-Claire/Cuisine et Vins de France. |

This iconic dish comes up constantly when one reads about French cuisine. A few years ago, I read an entire book of essays detailing the many ways the dish is prepared in various regions (blog post here: Pot-Au-Feu). In fiction, I've seen references by authors as diverse as Zola and Antoine Laurain. I have no doubt that Von Bremzen is right to identify pot-au-feu as the French national dish.

"A museum piece of a meal" --- What a fantastic description of the preparation of a meal.

ReplyDeleteI'm still thinking about the idea of Paris syndrome.

A pot of boiled meat and vegetables? With a fancy French name? I'll take it.

ReplyDeleteWow! what a great post. This book is so interesting. Thank you for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteThe meal in the last photo looks delicious, like something I could make in my slow cooker. he book sounds interesting, thanks for sharing. Have a great weekend.

ReplyDeleteYummy!

ReplyDeleteYes, the "problem" with French iconic dishes (and I belive it's the same with many other countries), is that twenty miles away, you can find a diferent recipe! And everyone is of course swearing they have THE authentic recipe, lol.

Same for instance with Bœuf bourguigon, Cassoulet, Choucroute garnie, and many more, I'll stop torturing your tasting buds here.

I had the feeling that pot-au-feu was no longer cooked by younger generations, especially living in cities, but I may be wrong.

But when I was a kid growning up in a tiny 250 inhabitant village, yes, that was a super common dish.

Sounds like a great book!

ReplyDeleteAnd... pot au geu! Something to remember for when there's a chill in the air again.

The name sounds fancy but the dish looks very basic and simple. I love the art work on the cover of the July 15, 1896 magazine- interesting post. Thanks Mae

ReplyDeleteThis is fascinating, Mae. What an intriguing sounding book.

ReplyDeleteImpressive and comprehensive review. I'm not much of a cook, but the photo looks yummy.

ReplyDeleteTerrie @ Bookshelf Journeys

One of the things that is an issue with trying to declare a national dish of any big country is the variation in diets in different regions of the country. The food and drink that we ate in the north of France was different to what we ate in Paris.

ReplyDeleteThis book sound interesting Mae. I am going to bookmark it. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThanks for this, I bookmarked it at the library.

ReplyDeleteJust as we have no "National cuisine" in America. That dish actually reminds me of a New England boiled dinner.

ReplyDeleteIt's fascinating how a "national dish" can vary by region, and even local dishes vary by city within a region. This cover of the book initially caught my eye (looks like a Roz Chast illustration) and it sure sounds like one for the wish list!

ReplyDeleteYummy sounding and looking dish. Something to remember for those colder winter meals.

ReplyDeleteSounds like a fascinating book--and my library has it! Thanks.

ReplyDeleteThe last time I was in Paris (pre-Pandemic now) I found eating well more challenging than I would have liked. I think so many undiscerning tourists means that restaurants can get away with whatever. (McDonald's, in Paris!) But we had an incredible meal in Uzés in a small restaurant run by such a lovely couple.

Wow. That's a fascinating book on national dishes and the histories behind what national can mean around the world. Thanks for sharing this. Definitely one I'd love to pick up!

ReplyDelete