What is a humanist? Sarah Bakewell’s introduction to her new book on this subject begins with this definition: A humanist is a person whose concern is “the human dimension of life … whereas scientists study the physical world, and theologians the divine one, humanities-humanists study the human world of art, history, and culture. Non-religious humanists make their moral choices based on human well-being, not divine instruction. Religious humanists focus on human well-being, too, but within the context of a faith. Philosophical and other kinds of humanists constantly measure their ideas against the experience of real living people.” (Humanly Possible, pp. 3-4)

In her introduction, Bakewell summarizes the long history of humanists:

“Through the centuries, humanists have been scholarly exiles or wanderers, living on their wits and words. In the early modern era, several fell foul of the Inquisition or other sleuths of heresy. Others sought safety by concealing what they really thought, sometimes so effectively that we still haven’t a clue. Well into the nineteenth century, non-religious humanists (often called ‘freethinkers’) could be reviled, banned, imprisoned, and deprived of rights. In the twentieth century they were forbidden to speak openly, told they had no hope of running for public office; they were persecuted, prosecuted, and imprisoned. In the twenty-first century so far, humanists still suffer all these things.” (p. 7)

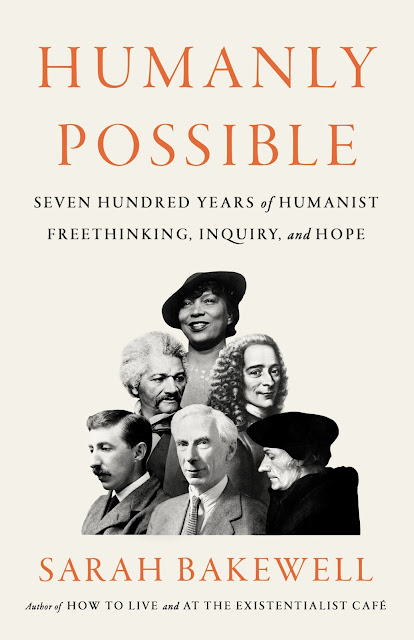

Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, which I have just begun reading, looks to be a fascinating book with interesting implications for the political events of the moment. More distantly, the development of humanist thought in Renaissance Italy has fascinated me for a long time, and I’m enjoying Bakewell’s account of the writers and philosophers of that era.

The review of this book in The Guardian published last week suggests the way the term “humanist” has emerged, particularly how the usage of the term humanism is more recent than the way of thinking that’s at the center of the book:

“To date the rise of ‘humanism’ to the early Renaissance is, strictly speaking, anachronistic; there was no such term until the 19th century. But Humanly Possible traces a lineage, less of theories than of kindred spirits, over seven centuries in Europe. This runs from medieval umanisti (students of humanity), who remained Christian even while resurrecting ‘the flowering, perfumed, fruitful works of the pagan world spring’ (as John of Salisbury called them), to today’s (more secular) self-declared humanists.”

Who is Sarah Bakewell?

Here is Sarah Bakewell’s picture, drawn by Brad Craft, as posted on her web page:

|

| From https://sarahbakewell.com/about/ |

A few things she says about herself:

“After fitful attendance at various schools, I studied philosophy at the University of Essex. I became enthralled by the work of Martin Heidegger and embarked on a PhD, but some impulse led me to give this up and move to London, where I found work in a tea-bag factory. My job was to catch boxes of tea-bags spat at me by a machine, flip them on their sides, and push them in groups of six to the next person on the line. It was only for the first two hours that the machine spat faster than I could flip, but those two hours were a formative influence.

“After this, I worked for several years in bookshops: Hatchards in Piccadilly, and Collet’s International in Charing Cross Road (the latter now long gone, alas). I did a postgraduate degree in Artificial Intelligence, then landed a job at the Wellcome Library for the History of Medicine. I spent ten fascinating years there as a cataloguer and curator of early printed books….

“Since 2002, my main job has been writing, although I also worked part-time for the National Trust from 2008-2010, cataloguing book collections in historic properties around England. I taught Creative Writing at London’s City University and Oxford’s Kellogg College for some years.

“Otherwise I live mostly in London, and enjoy the usual glamorous writer’s life: putting a comma in, taking it out, putting it back in again, and eventually deleting the whole sentence.”

I may write more about Bakewell’s new book as I continue reading it. I’ve very much enjoyed two of her other books on the topics of the Existentialists and the philosopher Montaigne. She’s becoming a favorite author of mine.

This sounds interesting, Mae. I liked her bio, too. She sounds like one of those writers who can take on in-depth subjects and make them accessible and interesting.

ReplyDeleteWho love knowing for its own sake with a love for humanity and utility. My heroes. May more of us be like them

ReplyDeletePeople are celebrating interesting people!

ReplyDeleteI liked both The Existentialist Cafe and How to Live, too. I will definitely look forward to hearing more from you about this book and, if you like it, I will probably read it.

ReplyDeleteI loved how she wrote about living the glamorous writer's life. I'm not sure I've ever known a true humanist as was defined.

ReplyDeleteI got an error trying to leave you a comment. Maybe blogger didn't like what I wrote!

ReplyDeleteI love especially the section from/about herself. Such a great start with the teabags.

ReplyDeleteGreat review of an excellent book. I too have followed Bakewell though her books and loved them all. Thank you!

ReplyDelete