I wrote this in 1999 after being in Cambridge, England, for several weeks, while Len was attending a workshop at the Isaac Newton Institute at Cambridge University. I was thinking of this long-ago experience when I watched a performance of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at Shakespeare in the Arb last week.

|

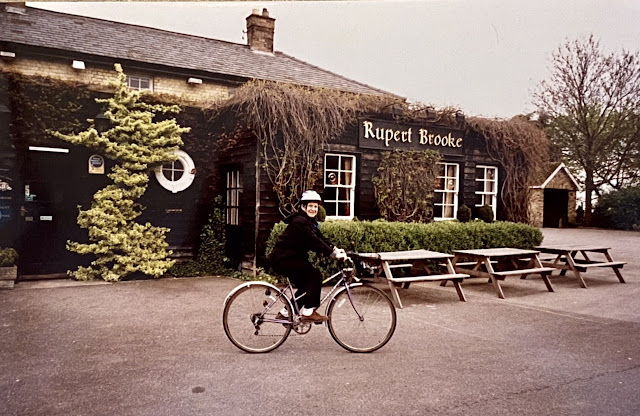

| 1999: Riding my bike in Grantchester, near Cambridge, England. |

Along the Cam river towpath watching the crews practice rowing, we left our apartment in Chesterton near Cambridge. We cycled towards Bait's Bite Lock. Pleasure boats use the lock by pushing a button to let water in or out. Cyclists push the bikes up a narrow ramp alongside the stairs to get to the other side of the river. From there, we began our ride through fields and past farm yards, using a distant power line with its tall steel pylons as a goal. At one point the track narrowed to a single beaten path across a field, not much wider than a single tire, marked by occasional stakes. The final trek followed a disused railway line, detoured around an old mill race, and entered a small town where Sunday family activities included loading furniture into station wagons, and doing bits of yard work in well-kept yards of substantial English houses.

After a short stretch of too-busy paved road, we reached the entrance to Anglesey Abbey, a stately home that long ago served as a religious building, so still is called an Abbey. The complex includes the usual large tourist facility, with a vast parking lot and a modern ticket-sales area including public restrooms and a cafeteria capable of seating several busloads of tourists. Inside the gates, the grounds extend northeast to the mill which we had circuited on our bikes, and west through a vast expanse of formal gardens and manicured woods.

We toured the mill as well as the house. Because of the proximity to appropriate water, the site has probably provided milling power since Roman times. The present building, much restored, has stood for a few hundred years. First a grain mill, and later a cement mill. No direct mention, but the disused railway line went right up to the mill, and must have been important for bringing in raw materials and taking away the milled gravel and cement products. Now, associations of young milling hobbyists run the mill on chosen weekends, as well as other mills in the area and throughout England.

Anglesey Abbey is in an English Fairy Tale setting. It invokes all kinds of half-remembered children's stories about the long history of small-statured immortal tribespeople who lived in these fields. The National Trust documentation and souvenir shop was more interested in selling tea towels, boxes full of miniature jam jars or chocolate bars, and monogrammed crockery than in offering any maps of local fairy rings. So use your imagination, call up your memories of fairy tales, of Shakespeare's Puck and his royal masters Oberon and Titania, of the Irish Pooka who came to America as Harvey the Rabbit in the Broadway play, and of the Welsh creature called

pwcck. They all wander on these long-trodden paths.

Above all, I am reminded of Rudyard Kipling's book, Puck of Pook's Hill. It begins with "Puck's Song."

Puck's Song

See you the dimpled track that runs,

All hollow through the wheat?

O that was where they hauled the guns

That smote King Philip's fleet.

See you our little mill that clacks

So busy by the brook?

She has ground her corn and paid her tax

Ever since the Domesday Book.

…

See you our pastures wide and lone,

Where the red oxen browse?

O there was a City thronged and known,

Ere London boasted a house.

…

She is not any common Earth,

Water or wood or air,

But Merlin's Isle of Gramarye,

Where you and I will fare.

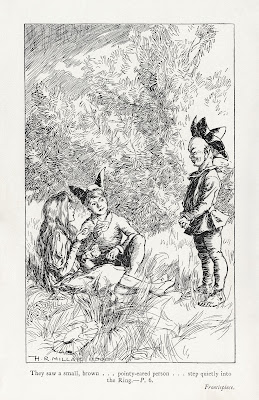

Throughout the story, Kipling interlaces little verses among the adventures of two children and their meeting with the short, ancient Puck, who doesn't want to hear the word "Fairies." They have called him out of the magical hills, especially his own, Pook's Hill, by acting, in a fairy ring, some scenes from Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream. A millstream ran nearby, its banks overgrown with plants. As it had for generations, the stream still carried water to a nearby mill.

Upon emerging and surprising the children, whose names were Dan and Una, Puck claims the land, and they dispute it, countering with their father's ownership. "I'm Puck, the oldest Old Thing in England, very much at your service if — if you care to have anything to do with me. If you don't of course you've only to say so and I'll go." They ask him to stay and share their biscuits, which he eats with salt, calling attention to the significance of his gesture. He borrows a knife, cuts a clod from the earth, and presents it to them ceremoniously, explaining that this makes the land theirs in a much more significant way. All the formalities over, he begins a tale of the Norse god later known as Weland, describing the god's arrival in England, his long stay while people worshipped him, and finally, his departure.

The first chapter of Kipling's Puck thus sets a scene that enchantingly calls up my experience at Anglesey Abbey and especially in the fields surrounding it, and the mill that it now owns (though the actual setting of Kipling's story is quite far from there.) While lots of other fairy tales evoke similar fields and streams, I find the childhood discovery described in this book to be the most appealing.

The main point of Kipling's book is imaginative retelling of certain key areas of English history. Puck represents the place: he sees all the others: Saxons, Romans, Normans, Jews — as newcomers. Kipling presents him as totally rooted. Unlike supernatural figures from other sorts of stories, Puck does not come from some mysterious or dangerous "other side."

I want to see Puck as Kipling's creation and prior to that as Shakespeare's creation. These literary figures are not folklore, though they owe their origin to folk tales where they are called Pucks or Pookas. (Also in another literary creation, the play "Harvey," the chief but invisible character is a human-scale rabbit named Harvey, identified as a Pooka, or mischievous but harmless character from Welsh and Irish myth.)

In reading Puck of Pook's Hill, I was astonished that Puck/Kipling depicted a figure from medieval Jewish history as a key to understanding the events of the twelfth century. I waver between fascination and dislike for the characterization of Kamiel, the Jew who has the gold -- and I'm particularly unfond of Kipling's poem attributing possession and love of gold to a Jewish destiny. However, I do love the character Puck in both Shakespeare's and Kipling's works.

Text © 2022, 1999, mae sander.

Love the post. We were in England in 1999 but only for 3 weeks. Wouldn't that have been something if we'd crossed paths that long ago - ha!

ReplyDeleteThat must have been a fun experience. I like the photo of your riding your bike.

ReplyDeleteToday we shall be visiting Stratford-upon-Avon. I've never been to Cambridge and this visit is too short to include it. Maybe next time?

ReplyDeleteWhat a fabulous post. I felt like I was with you in your cycling journey and as you wandered through Anglesea Abbey. I wasn't familiar with Kipling's Puck, only Shakespeare's, so this might have even been the most delightful part of all. What a glorious time!

ReplyDeleteWhat an amazing experience you must have had. I loved the photo of you on your bike in Grantchester. Reminds me of scenes from Midsomer Murders. This must have been fascinating.

ReplyDeleteI have also not read Puck, so I feel rather illiterate when you compare Kipling to Shakespeare. I appreciate the read, though.