Not Much Cooking!

New Utensils

New Magnets

|

| I removed many magnets to make room for my new ones. |

|

| New magnets from Greece and Turkey. You can see what I found: mainly images of birds, especially owls. You can also see that my little plant survived my absence. |

A Few Meals Before the Big Trip

The Ship's Kitchen

|

| The door to the ship’s kitchen. |

“My kitchen” this July means not only the kitchen where I live in Ann Arbor, but also the kitchen of the National Geographic/Lindblad Orion where we spent 10 days while visiting Greek islands in the Mediterranean and three ancient sites in Turkey.

|

| A peek down the stairs towards the extensive storage areas for food and equipment. |

|

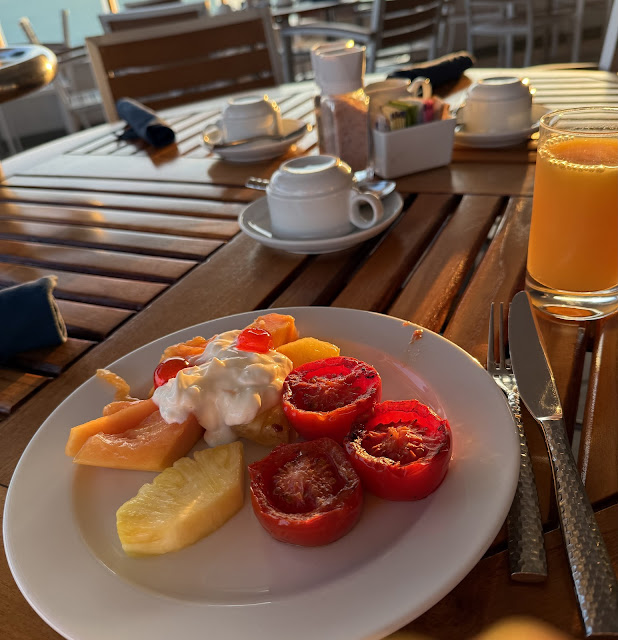

| Just before breakfast: the waiters would bring the food from the kitchen up to the dining area on the rear deck. |

What Kitchen Did this Come From?

Blog post © 2025 mae sander

Shared with Sherry’s In My Kitchen for July